Commercial data brokers

Commercial data brokers collect and sell information about us collected from photos posted to social media, historic geolocation data collected by our cell phone apps, banks, credit agencies, purchase history, education records, employment records, property records and real-time location.Footnote 1 These data points are among billions archived in public and private sources. This personal data is mined by third-party vendors and data resellers, then aggregated and analyzed by data brokers who in turn look for buyers of its troves of profiles.

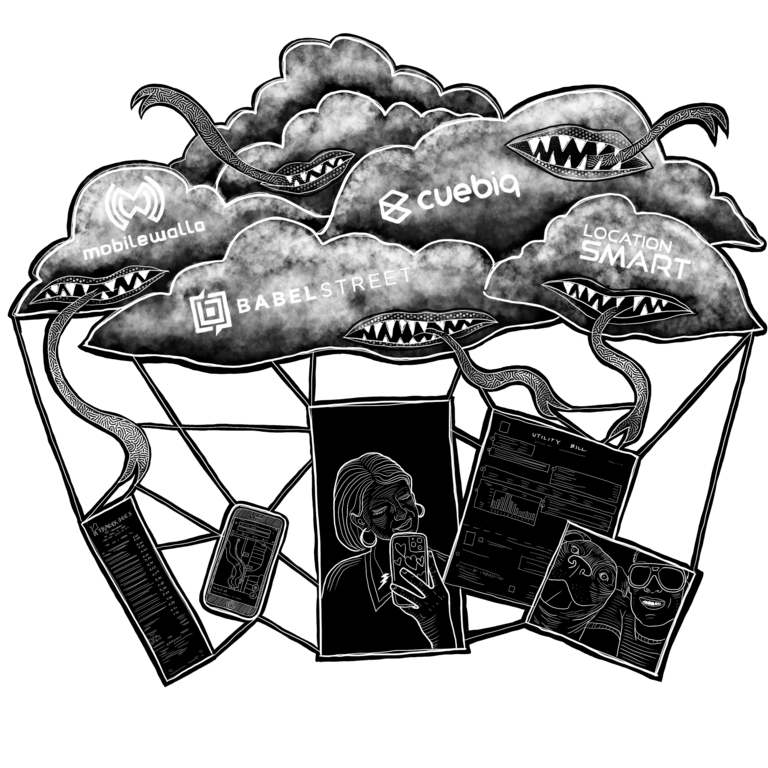

If you have a cell phone, you are being stalked and your personal data sold by multiple companies whose names you’ve likely never heard.Footnote 2 So-called “third-party vendors” or data brokers like Venntel, Babel Street, Cuebiq, and LocationSmart collect real-time location data via GPS.Footnote 3 They monitor your activities and movements through your phone via benign-seeming apps that use software development kits, or SDKs.Footnote 4 Apps that use SDKs include weather apps, exercise monitoring apps, and video games.Footnote 5 Third-party vendors provide SDKs to app developers for free in exchange for the information they can collect from them, or a cut of the ads they can sell through them. The aggregate information that apps collect can be extremely revealing. One third-party vendor, Mobilewalla, claimed to be able to track cellphones of protesters, and said it could identify protesters’ age, gender, and race via their cell phone use.Footnote 6 Historical location extracted by a data vendor from the gay hookup app, Grindr, was used by two reporters to “out” a top Catholic Church official.Footnote 7

Law enforcement purchases criminal history reports, financial data from credit bureaus, and other personal data to profile people.Footnote 8 For example, CBP purchases access to the Venntel global mobile location database via a portal, so that CBP officers search a Venntel database to look for addresses or cell phone numbers.Footnote 9 DHS can also access cell phone location history from private databases that sell subscriptions or search platforms, such as LexisNexis and TransUnion.Footnote 10

Some experts have noted that “anonymized” GPS location data is notoriously easy to cross-reference.Footnote 11 A New York Times op-ed posed the question: “Consider your daily commute: Would any other smartphone travel directly between your house and your office every day?” The authors concluded: “In most cases, ascertaining a home location and an office location was enough to identify a person.”Footnote 12 More recently, cell phone location “pings,” collected by apps and stored under profiles tied to mobile ad IDs that are assigned to smartphones, were sufficient to identify individuals who ransacked the Capitol building in Washington, D.C., on January 6.Footnote 13 And the use of “geo-fencing,” i.e. obtaining information from private companies about all persons in an area at a given time, has become exponentially more common in recent years.Footnote 14

As long as surveillance capitalists and others are permitted to steal and sell our real-time and historical location data, this information will be available to anyone who can buy it — including DHS and other government agencies.Footnote 15

Today, we as a society are just beginning to ask questions about the commodification of personal data and the implications of having our behaviors constantly predicted and used as fodder to improve future predictions. Within the prison abolitionist movement, we are familiarizing ourselves with RATs (risk assessment tools) used in the pretrial criminal process to deny or grant money bail. In the migrant justice movement, we know that DHS and other law enforcement agencies circumvent the hassle of judicial search warrants by simply buying personal data from commercial vendors.

This practice isn’t new: A good two decades before ICE figured out that it could buy location data from commercial third-party vendors, DHS’ precursor, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), was by 1998 digitally stalking airline travelers using records created by online airplane ticket purchases, and profiling them based on their ticket-purchasing habits.Footnote 16 See PNR.

After 9/11, the federal government ramped up its data-collecting, database-sharing, automated predictive threat modeling and terrorist risk profiling. It beefed up its biometric identification technologies and partnerships with commercial entities that secretly collect, retain and sell consumer data for profit. The World Trade Center attacks allowed the government to exceptionalize sites of travel (especially international flights) as deserving of extreme surveillance; meanwhile, big data collection and analysis industries, facilitated by growing Internet and cell phone use, were handed billions of dollars in research and development funds, and enjoyed little to no oversight as they churned out new data-collecting and prediction technologies. The US government spent at least $2.8 trillion on counterterrorism related efforts between 2002 and 2017, granting contracts to old time war profiteers like Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman — but also to Silicon Valley technology giants such as Amazon, Google, and Palantir Technologies.Footnote 17

Today, commercial data collected by airlines are stored and mined by various DHS data systems to look for patterns, predict “risk” and “identify abnormalities in travel patterns.”Footnote 18 Privately-owned and contracted vendors provide new, state-of-the-art, cloud-based data visualization, AI tools and interfaces that seamlessly integrate with other commercial datasets to make sense of the massive, constantly-expanding data pool of location and behavioral data collected by private aggregators and public records.

DHS data systems that rely on commercial data brokers

At the Pacific Enforcement Response Center (PERC), contract analysts cross-check multiple criminal legal and DHS datasets against commercial databases like LexisNexis, seeking to identify and locate people who might be deportable. Ironically, data fed into commercial data aggregators is often recycled, itself coming from numerous government and other commercial databases.Footnote 19 These include real-time incarceration records (including booking photos), cell phone location and automated license plate reader data history, home address and Social Security information from Equifax, and social media accounts.

Likewise, ICE uses its Operations Management Module, or OM² — part of the EID system — to perform manual and batch address checks of ICE’s “leads” against US Postal Service commercially available data sets that update city and state information by zip code. OM² cross-references those data against commercial sources that provide open source data that includes biographical information, criminal history, criminal case history, and vehicle information (including vehicle registration information). It includes “phone numbers of targets associated with the lead.”Footnote 20

Other predictive tools, such as DHS’ AFI, provide geospatial, temporal and statistical analysis, and advanced search capabilities using commercial databases and Internet sources, including social media and traditional news media.