Surveillance Capitalism, Surveillance Carceralism

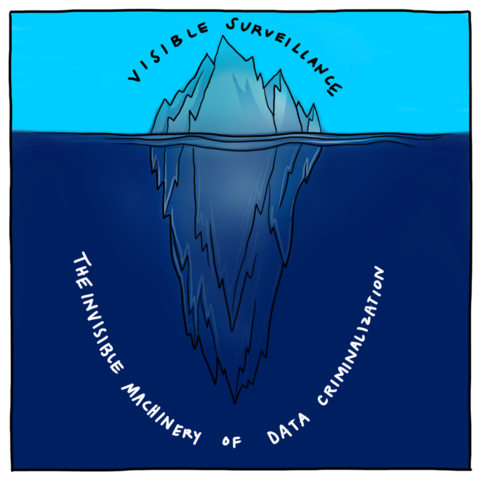

View full-page version for printing Table of ContentsVisible Surveillance, The Invisible Machinery of Data Criminalization

Generally, the surveillance that we can see make up the tip of an iceberg:

- You receive a Facebook message from a stranger whose account has a profile photo of a dog. The writer says that they want to meet up and buy a piñata that you’re selling. An ICE officer greets you in the parking lot.Footnote 1

- The salesperson at the car lot refuses to sell you a car after running a credit check and finding that TransUnion, a credit reporting agency, flagged your name as a “potential match” for one on the Treasury Department’s watch list for “terrorists, drug traffickers and other criminals.”Footnote 2

- The highway patrol officer who just ran your license decides to detain you, based on the automated alert that he received that alleges that you were previously deported.Footnote 3

- ICE agents arrive at the airport gate before you catch an international flight.Footnote 4 A computer system identified you as a risk for having overstayed a visa.Footnote 5

- ICE shows up at your non-immigration-related court appointment.Footnote 6

- A detainer and an administrative warrant are served to a jail, asking the Sheriff to notify ICE when you’ll be released.Footnote 7

- You receive an order of removal.Footnote 8

For every one of those encounters there is much unseen: troves of data sorted and choices made by algorithms, dozens of analysts and agents, billions of dollars in contract vendors, a daisy-chain of computers and communications systems and interoperable software programs, mirrored datasets and cloud servers, a miasma of agencies and interfaces.

Today’s sprawling surveillance machinery of immigrant criminalization was built over decades, drawing from centuries of racialized capitalism and social control, anti-blackness, settler-colonial expansionism, and US imperialism.

Through evolving surveillance practices of data criminalization, the US government creates and uses data as both justification for and a means to criminalize US non-citizens. The term “crimmigration” refers to the intersection of criminal and immigration laws in the US, especially since the 1990s, to punish non-citizens in the US differently and more harshly.Footnote 9 Crimmigration developed alongside and as part of mass incarceration. The artifacts and outcomes of that “crimmigration” history is preserved in numerous people’s “permanent records” in legacy and cutting-edge government databases, and in data-sharing protocols built into law enforcement technology and communication tools.Footnote 10

These databases are not just an archive; they are an arsenal.

These databases are not just an archive; they are an arsenal. New prediction and profiling technologies contracted by DHS grow the agency’s migrant surveillance dragnet by dredging up decades-old, often forgotten data (including data not originally intended to criminalize, such as naturalization and passport application records) and gives that data new life to criminalize by matching them with previously unlinked criminal records and newer forms of invasive biometric identification and location-tracking databanks. But a “match” to criminal records, flagged by an event such as international travel, or getting stopped by a cop, is no longer the only path to immigrant criminalization.

...a “match” to criminal records, flagged by an event such as international travel, or getting stopped by a cop, is no longer the only path to immigrant criminalization.

In DHS’ newer data-sorting mechanisms, artificial intelligence (AI) tools are capable of scanning millions of database entries, collecting new data, creating “profiles” of individuals, linking them to others, and using so-called predictive analysis to sort people categorically for ICE to monitor and revisit based on assigned levels of “risk.”Footnote 11 And, for as many dollars as have been invested into databases, analysts, and prediction, there are even more errors and omissions. Records are flush with name misspellings, outdated naturalization records and incomplete adjudication records. ICE has stated that there are a few million people who "derived' citizenship (people who were not born in the US but became citizens at birth, or at some point while still a minor, because of their parents' status), whom DHS databases would flag as non-citizens based only on their birth abroad.Footnote 12 Police are able to include in gang databases anyone that they want. Gang databases list deceased people and infants as members.Footnote 13 Data analyses are often incorrect, relying on outdated or inaccurate data, and they have outsized impact. Each past “encounter” that a person has had with a customs agent, immigration officer, or cop creates lasting vulnerability and exposure that can be reactivated if a person falls into a category (for instance, naturalized citizens, current visa holders, non-citizens, or people who are “removable” by ICE) that are flagged for increased scrutiny by DHS. Categorically targeted people are added to various databases who will be automatically and constantly tracked, profiled and evaluated for deportability — as well as disciplined by being denied public benefits, workplace protections and other access to rights.

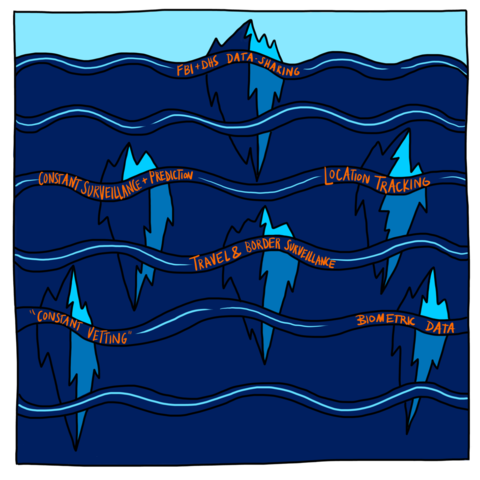

FBI & DHS Data-Sharing, Constant Surveillance and Prediction, Location Tracking, Biometric Data, "Constant Vetting", Traveler and Border Surveillance

We are at a crossroads

In the following sections, we examine how key law enforcement databases have been connected and updated for decades, noting potential targets in these automated, linked systems. We describe the significance of DHS’ move from a suspect-based “watchlist” model to a big data model, monitoring massive numbers of individuals in real time and circumventing legal and all other oversight by buying GPS and cell phone location data, utility bills, DMV records, Internet search history,Footnote 14 change-of-address records, social media interactions, and other personal information that is routinely sold to government agencies by commercial vendors. We name some common points of data extraction, old and new. We also provide an overview of traveler and US border surveillance since the late 1990s, because monitoring techniques for international travel have been at the forefront of data criminalization and surveillance and may foretell the next decade of immigration and criminal punishment enforcement technologies.

DHS's digital surveillance system is still in its infancy, and thus seemingly inefficient.Footnote 15 Despite the vast amount of resources that DHS receives, since its inception the agency has been plagued by rivalries, bureaucracy, high turnover and lack of consistent leadership due to changes in US presidential administrations.Footnote 16 One former management-level DHS employee noted that at the time of its creation, “DHS wasn’t even a loose confederation of agencies, back then it was more like rogue nations that happen to find themselves on the same continent.”Footnote 17 Conflicts between sub-agencies (“DHS Components”) have prevented seamless database merging.Footnote 18 And logistical problems persist. ICE needs to physically locate a person in order to arrest and potentially deport them. Deportation can be a time-intensive process. ICE officers have large caseloads and need to work with embassies and consulates to obtain travel identification documents, such as birth certificates and passports, which permit ICE to deport a person.Footnote 19 Despite the billions of dollars ICE spends on sophisticated spying, data visualization, indexing and prediction tools, the process of deporting people from inside of the US can still require accessing standardized criminalization data and engaging in a bureaucratic legal process.

Court records show that one of DHS’ major criminalization hubs, the Pacific Enforcement Response Center (PERC) — which hires analysts to work 24/7 and use top-of-the-line data-scraping and social-mapping tools to find people who might be deportable — issued nearly 50,000 detainers in FY 2019.Footnote 20 Yet, “trial evidence nevertheless indicated that ICE does not take into custody up to 80 percent of the individuals for whom PERC issues immigration detainers.” Recent data collected by Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) confirm the pattern.Footnote 21

What happens in those 80 percent of cases, and why?

We posit four theories:

- By trawling so wide, ICE’s automated data criminalization process is creating more work for deportation officers than is possible for them to do, creating opportunities for DHS to justify its continuous expansion

- The legacy criminal legal, visa and naturalization data that ICE requires to prove deportability has not yet been updated and fully integrated into the new systems of data criminalization

- It is possible that DHS’ goal is not only mass deportation, but also the indexing and management of a permanent subclass of migrant workers who are systematically excluded from rights and will be findable whenever deportations are deemed politically necessary

- Migrants are being used to test techniques and set precedents that will eventually be used for continuous monitoring and control of everyone in the US, including US citizens.

DHS has long been moving toward centralizing and linking information from all its and other government databases, and automating the process that predicts, biometrically identifies, profiles and tracks in real time the location of any foreign-born individual who has come to the US. As part of an ever-expanding, lucrative data market, hundreds of legacy war profiteers and start-ups are available to help develop the next generation of tech tools to do this targeting for the US government.

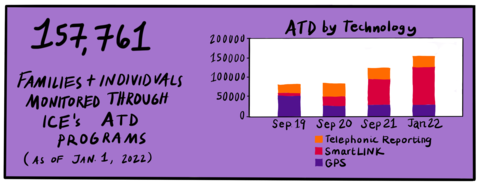

Ankle monitors, SmartLINK, and beyond: Case study of an iceberg

In this section, we look at ISAP, ICE’s “alternative to detention” (ATD) program which functions as a surveillance tech and social control program. As a movement, we have spent much of our energy fighting the requirement that ISAP “participants” wear GPS-enabled ankle devices. However, ankle monitor technology is falling out of favor within ISAP — and our years-long focus on them has deflected attention away from other forms of location-tracking and data criminalization practices that may be more insidious than shackles. Finally, as we will see, programs like ISAP show that while triangulation by the criminal punishment apparatus and the immigration system is still the most comprehensive way to enforce migrant exclusion, government programs that index “vulnerability” and dispense “services” are often conscripted to spy on and police its “clientele.”

As a movement, for years we have sought to understand, expose, and seek legislative containment or abandonment of individual technologies and programs that make up the iceberg tips in the surveillance landscape. We are coming to realize that mechanisms for tracking and control are networked to and siphon from millions of other data points, which are analyzed by multiple connected systems. Targeting a specific program or technology may not have much impact on the functioning of the larger apparatus — and this is especially true as commercial technologies normalize surveilling all of us, not just migrants, or people in the criminal legal system.

Targeting a specific program or technology may not have much impact on the functioning of the larger apparatus — and this is especially true as commercial technologies normalize surveilling all of us, not just migrants, or people in the criminal legal system.

For example, in recent years, many migrant justice organizers noticed an uptick in migrants — especially asylum seekers — being made by ICE or immigration judges to wear location-tracking ankle monitors, which use either radio frequency or GPS technology.

These devices are part of ICE ERO’s “Alternatives to Detention” (ATD) program, ISAP (Intensive Supervision Appearance Program), which began in 2004. ISAP has mostly been contracted out by ICE to a private company, Behavioral Interventions (B.I.) — a subsidiary of the private prison corporation, GEO Group. People enrolled in ISAP may be monitored for ICE by technologies including: telephonic reporting that uses voice recognition software, location tracking via ankle shackles, or a smartphone app (SmartLINK) that uses face and voice recognition to confirm identity as well as location via GPS monitoring.Footnote 22 For most ISAP “participants,” the “case worker” or "probation officer" they must report to is a B.I. employee.

ISAP was once a conditional release program that gave people with criminal records a way to bond out from immigrant jail.Footnote 23 But by 2015, the government had implemented a policy of categorically enrolling asylum-seekers in ISAP — these were mostly families from Central America who passed “credible fear” screenings, and are in deportation proceedings but on the “non-detained docket.”Footnote 24 For its part, DHS is clear that ISAP, its main ATD program, “is not a substitute for detention, but allows ICE to exercise increased supervision over a portion of those who are not detained.”Footnote 25 ISAP “uses technology and other tools to manage alien compliance.”Footnote 26 In other words, ISAP is a surveillance tech and social control program, and net-widener. ISAP grew throughout the years, and at this point, there are far more immigrants in ISAP than there are detained in immigration jails.Footnote 27 Based on the most recently available data, ICE has at least 3.3 million people on its non-detained docket.Footnote 28 Of those, roughly 118,000 are subject to e-carceration.Footnote 29 An additional 26,000 are incarcerated in ICE jails.Footnote 30

The ankle devices use two main technologies. Some rely on radio frequency (not GPS) to monitor a person on house arrest, and require the wearer to have a landline telephone. Other ankle shackles use GPS monitoring to track a person’s movements, which have to be pre-approved by the B.I. “case worker.”

There are many reasons to be alarmed by the location-tracking capabilities of these shackles. In August 2019, ICE used geolocation data from ankle monitors to obtain a warrant for and plan a mass deportation from two towns in Mississippi.Footnote 31 The result was the largest single-state worksite raid in US history. It is very possible that data recorded by geolocating devices will again be used to collectively punish families and entire communities.

But onerous and dehumanizing as they are, ankle monitors make up a shrinking proportion of ISAP, and of migrant surveillance overall.

But onerous and dehumanizing as they are, ankle monitors make up a shrinking proportion of ISAP, and of migrant surveillance overall.Footnote 32 Technologies are always being upgraded. ATD statistics bear out the trend: one city at a time, the numbers in the category “SmartLINK” are overtaking those in “GPS.” The category names are misleading, since the SmartLINK cell phone app has provided a platform for much more expansive forms of data theft than ankle monitors allowed for — using GPS tracking as well as face and voice recognition technologies to surveil those who, as part of enrollment in ISAP, are forced to use the app.

Due to the hidden way that cell phone apps track people, this real-time location and biometric data theft does not generate the outrage that it should.

Source Footnote 33

ATD by Technology, Monitored through ICE's ATD Programs, Telephonic Reporting, SmartLINK, GPS

ISAP numbers reveal a larger story of data criminalization: While there is continuing and growing interest within the migrant justice movement in ankle shackles and the ISAP program, new forms of surveillance could make ankle monitors obsolete. They are replaced by other methods of location data gathering and data scraping which are more seamless and can be easily merged with legacy criminalization tools and processes.

And although ICE’s ATD program has grown (from 83,186 people enrolled in 2019, to 85,415 in 2020, and 136,026 in October 2021), the information collected by ISAP may also become irrelevant as DHS refines and expands its surveillance and social control systems to ensnarl more people in less formal, less visible and more frictionless ways. The story of ISAP III within immigration surveillance is cautionary on multiple fronts: Although immigration activists and advocates have long fought against ICE’s use of ankle monitors, cell phone tracking is far more onerous and invasive than ankle monitors.

The story of ISAP III within immigration surveillance is cautionary on multiple fronts: Although immigration activists and advocates have long fought against ICE’s use of ankle monitors, cell phone tracking is far more onerous and invasive than ankle monitors.

DHS continues to pilot new technological surveillance devices, such as one to track people in real time while they are still incarcerated.Footnote 34 Border Patrol is currently testing the “Subject Identification Tracking Devices (SID):” “tamper-resistant barcode wristbands for tracking and identifying subjects.”Footnote 35 Another smartphone app, CBP One, was tested in late 2020 and is expected to become a main platform for travelers entering the US to submit geo-tagged photographs to CBP for real-time “vetting.”Footnote 36 There is no end to pilot programs and contract vendors, and as long as we focus exclusively on the latest iterations of these, we may miss the bigger picture.

There is no end to pilot programs and contract vendors, and as long as we focus exclusively on the latest iterations of these, we may miss the bigger picture.

A constantly expanding net

There are an estimated 11 million undocumented migrants living in the US today. While I-9 work visa “no-matches” and data provided to ICE by government agencies like state Departments of Motor Vehicles and the US Postal Service flag some individuals for ICE scrutiny, it is generally entanglement with the criminal legal system, triggered by police harassment and arrest, that creates vulnerability for ICE arrest. While the 3 million undocumented people on the “non-detained docket” named above are especially vulnerable to ICE arrest and deportation if they have an encounter with a cop or miss a court date, ICE and DHS are constantly creating new ways to formally exclude migrants from rights and scale up monitoring, controlling, punishing, and potentially deporting all 11 million. In addition to undocumented migrants—who are constantly targeted by ICE—data criminalization also targets the approximately 13.6 million people who are here green card holders (“permanent residents”).Footnote 37 A final group likewise targeted through data criminalization is the more than 80 million temporary visitors who enter the US on tourist, student, or temporary work visas each year.Footnote 38

While the 3 million undocumented people on the “non-detained docket” named above are especially vulnerable to ICE arrest and deportation if they have an encounter with a cop or miss a court date, ICE and DHS are constantly creating new ways to formally exclude migrants from rights and scale up monitoring, controlling, punishing, and potentially deporting all 11 million. In addition to undocumented migrants—who are constantly targeted by ICE—data criminalization also targets the approximately 13.6 million people who are here green card holders (“permanent residents”). A final group likewise targeted through data criminalization is the more than 80 million temporary visitors who enter the US on tourist, student, or temporary work visas each year.

In the past few decades, the “crimmigration” system has expanded categories of deportable offenses and increased penalties for — while stripping protections from — migrants and non-citizens. DHS is constantly expanding the number of data sources it can use to create and maintain profiles of as many people as possible, so that it can automate and continuously identify people for arrest and deportation, or for other purposes such as criminalization in the name of anti-terrorism. At this point, newer immigration enforcement technologies operate largely in a world of speculative big-data prediction — which, coupled with unchecked, ubiquitous data-collection in everyday life, has the potential to vastly expand the pools of people whom are constantly “vetted” by ICE from a few million migrants who are already on ICE’s radar, to potentially all foreign-born people in the US, including those who have mostly flown under the radar because they haven’t gotten stopped or arrested by police. Whether or not deportation is actually DHS’ end goal, through criminalization and surveillance, people within this pool are systematically made vulnerable to exploitation in almost every meaningful way.

At this point, newer immigration enforcement technologies operate largely in a world of speculative big-data prediction — which, coupled with unchecked, ubiquitous data-collection in everyday life, has the potential to vastly expand the pools of people whom are constantly “vetted” by ICE from a few million migrants who are already on ICE’s radar, to potentially all foreign-born people in the US, including those who have mostly flown under the radar because they haven’t gotten stopped or arrested by police.

Beneath the surface

The technologies that surveil all of us enact disproportionate violence and harm on some of us more than others. Footnote 39

Most of us are aware that our cell phones and apps record our biometrics, track our movements, and private companies sell our location, biometric and behavioral data to marketers and data aggregators, who in turn sell to various government agencies.Footnote 40 Many of us seem willing to believe the industry claim that these data are anonymized — they’re not — and trade some amount of privacy for technologies that promise us new experiences, access to information and connections with others.Footnote 41 A 2019 Pew Research Center survey found that six out of ten people polled said that they did not think it is possible to go through daily life without having data collected about them by companies or the government.Footnote 42 Although 79% of respondents reported being concerned about the way their data is being used by companies, 81% also said that the potential risks they face because of data collection by companies outweigh the benefits, and 66% said the same about government data collection.

The issue isn’t that we’re being watched without our consent, or that things are aggressively being sold to us, says social scientist and scholar, Shoshana Zuboff. She argues in her book, Surveillance Capitalism, that our collective dispossession and overwhelm is due to the fact that this growing economic and technological regime is so encompassing and unprecedented that we are unable to understand its true dangers and implications. Instead, as a society, we lean on old tools, such as privacy and antitrust laws, which fail to comprehend the scope and nature of the problem.Footnote 43

Surveillance capitalism, Zuboff argues, describes how our daily lives are being mined as data for behavioral prediction and control. What its outcomes can look like, Zuboff wrote, is when your car shuts off if it detects alcohol on your breath.Footnote 44 Other real-world examples abound, she explained in a NY Magazine interview: “[I]n the insurance industry, in the health-care industry, insurance companies are using telematics so they know how you’re driving in real time, and can reward and punish you with higher and lower premiums in real time for whether or not your driving costs them more or less money, or whether or not your eating costs them more or less money, or whether or not your exercise patterns cost them more or less money.”Footnote 45

Zuboff makes the point that when executives at Google and Facebook claim that surveillance and tracking are part and parcel of their technologies and can’t be disabled, they are lying. But it is also true that the Internet itself was developed by profit-seeking contractors hired by the US military to not only communicate after a nuclear blast, but also to subordinate rebels abroad and at home in the fight against the perceived global spread of communism.

Zuboff makes the point that when executives at Google and Facebook claim that surveillance and tracking are part and parcel of their technologies and can’t be disabled, they are lying. But it is also true that the Internet itself was developed by profit-seeking contractors hired by the US military to not only communicate after a nuclear blast, but also to subordinate rebels abroad and at home in the fight against the perceived global spread of communism. As Yasha Levine wrote in his book, Surveillance Valley,

The Internet came out of this effort: an attempt to build computer systems that could collect and share intelligence, watch the world in real time, and study and analyze people and political movements with the ultimate goal of predicting and preventing social upheaval. Some even dreamed of creating a sort of early warning radar for human societies: a networked computer system that watched for social and political threats and intercepted them in much the same way that traditional radar did for hostile aircraft. In other words, the Internet was hardwired to be a surveillance tool from the start.Footnote 46

Then and now, many police departments have been eager to test militarized prediction technologies on civilian populations, seeking to aggregate as much data as possible and making special use of seemingly besides-the-point information gleaned from “field interviews” (police stops of non-suspects meant to mine individuals for information) in order to map and archive for future analysis any patterns or potential relationships between individuals (including those without criminal records), locations, and cars, for instance.Footnote 47

Gotham, one such data organization and predictive computer system, was created by the Silicon Valley company, Palantir, and used by the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD). (Palantir has also created tools especially for DHS, which are detailed later.) Gotham is supplemented with what sociologist Sarah Brayne calls the secondary surveillance network: the web of who is related to, friends with, or sleeping with whom.Footnote 48 In her book, Predict and Surveil, Brayne describes how one woman listed in Palantir’s system wasn’t suspected of committing any crime, but was included because several of her boyfriends were considered by LAPD to be within the same network of associates. Brayne, who spent more than two years embedded with the LAPD, noted that in order to expand its datasets, the LAPD also explored purchasing private data, including social media, foreclosure, toll road information, camera feeds from hospitals, parking lots, and universities, and delivery information from Papa John’s International Inc. and Pizza Hut LLC.

This is the context in which ICE data-stalks immigrants today.

What’s old is made new again

Nearly each month a new headline seems to reveal another invasive way that DHS tracks immigrants, often by using data created by spying on people during their mundane and seemingly private moments. ICE collects cell phone location history;Footnote 49 ICE analyzes family photos posted to social media, records location “check-ins” to places like Home Depot, siphons personal information like Social Security numbers and home addresses from credit agencies (who receive this data from banksFootnote 50 and before October 2021, utility companies);Footnote 51 and follows a person’s commute in real-time as automated license plate readers locate their car via surveillance cameras installed in public space and on private properties.Footnote 52 These data points are among billions archived in public and private sources, alongside lawsuits, credit scores, bankruptcy records, medical records, and purchase history. This personal data is mined by third-party vendors and data resellers, then aggregated and analyzed by data brokers who in turn look for buyers of its troves of profiles. This is the nuts-and-bolts of Zuboff’s surveillance capitalism machinery.

Migrants are subject to additional layers of surveillance, which converts into cumulative opportunities for criminalization. Simply being Black or Latinx creates risk for a police encounter.Footnote 53 The police stop itself leads to active, present-tense criminalization — an arrest, booking, jail custody, possibly a criminal case. A police encounter as well as incarceration have profound immediate consequences that increase a person’s risk of death.Footnote 54 They also create the material for ongoing data criminalization, which is future-oriented and compounding.

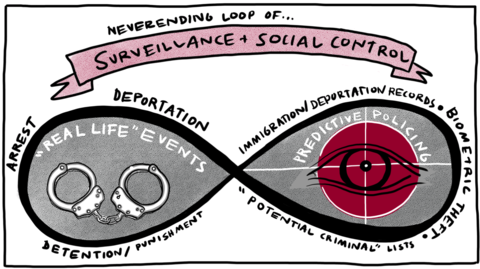

Data criminalization uses records that police and courts generate about you (your “criminal history”) to prove that you are a present or future “risk.” Community organizers working to end pretrial detention are intimately familiar with how a self-perpetuating feedback loop of data criminalization is created in the pretrial system by “risk assessment tools,” or RATs.Footnote 55 Pretrial RATs range from simple checklists to secret and complex prediction algorithms that calculate “risk” by using extra-legal data — such as so-called “failures-to-appear” in court, not having a cell phone number, and having been arrested at a young age — as derogatory variables that will automatically lead an assessment to recommend detention, a higher bail, or harsher conditions of supervised release. Using the technocratic assumptions of criminology and paternalistic language of social work, RATs use old criminal history and extra-legal data to punish and evaluate people accused of crimes. Old arrest data that didn’t lead to convictions are weaponized by RATs to predict not only a person’s “risk” of not showing up in court, but of generalized “violence.” These "violence" or "public safety risk" measurements are often conflated with generalized risk of arrest for any offense. RATs allow for allegations of missing a court-mandated therapist appointment, or an uncorrectable clerical error on a person’s “permanent record” to be dredged up again and again, enacting cumulative violence and reinforcing the narrative of a person being a “risk.” These pseudoscientific “risk assessments” provide the veneer of being objective and “data-driven,” all the while the slipperiness and undefinability of “risk” allows for and recommends extra-legal punishments and weaponizes datasets that are deeply flawed. Besides criminal legal data being inherently biased due to racist policing practices, what counts as “failure to appear,” for instance, is inconsistently calculated and ranges across jurisdictions; most criminal legal datasets generally are incomplete, outdated or inaccurate, and it may be difficult or impossible to challenge historical derogatory data.Footnote 56

Using the technocratic assumptions of criminology and paternalistic language of social work, RATs use old criminal history and extra-legal data to punish and evaluate people accused of crimes.

Data criminalization and automated processes make up the backbone of immigration enforcement today.

Neverending Loop of... Surveillance and Social Control, "Real Life" Events: Arrest, Deportation, Detentions/Punishment, "Predictive Policing": Immigration/Deportation Records, Biometric Theft, "Potential Criminals" Lists

For those of us who are immigrants, an expanding assortment of AI tools for data scraping and “continuous vetting” profile and identify us individually, and sort us categorically. Instead of relying on historical triggers, like entry into the US, or an arrest, the new systems not only make us visible to ICE at moments when we are most vulnerable — booked in jail, crossing a national border, or when a visa expires — but all the time. This method of surveillance aims to know not just those things about you that are conventionally thought of as potentially criminalizing (such as previous charges, convictions, migration and court records) — but everything about you: who your family, friends and community are, what you buy, where you buy it from, who you live with, where the car registered to your name is parked, what seat you chose on your last flight, your sleep patterns, how many hours a day you scroll through Instagram, what your utility bills are, and what you think (based on status updates, eye movements and heart rate).

Instead of relying on historical triggers, like entry into the US, or an arrest, the new systems not only make us visible to ICE at moments when we are most vulnerable — booked in jail, crossing a national border, or when a visa expires — but all the time.

But as sophisticated and automated as surveillance techniques may be, in order for ICE to deport a person, ICE still requires the bread-and-butter criminalization data generated from police encounters, and to match a person to official records in order to verify identification.

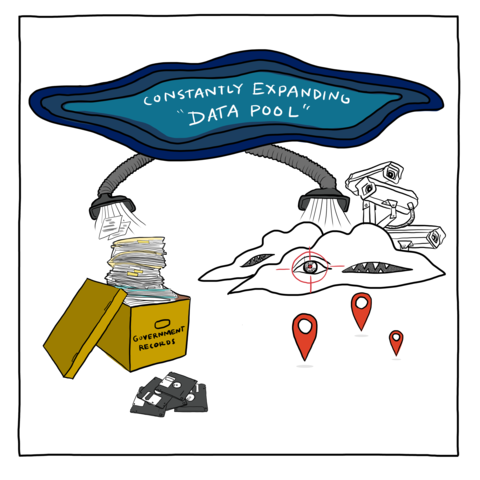

This means that immigration data criminalization siphons from two simultaneously operating systems: One system features privately-owned and contracted vendors that provide new, state-of-the-art, cloud-based data visualization, AI tools and interfaces that seamlessly integrate with other commercial datasets to make sense of the massive, constantly-expanding data pool of location and behavioral data collected by private aggregators and public records. The other is a system of government records, spread across multiple agencies, often duplicated or unmerged, unevenly maintained, sometimes sparse, outdated, and accessible primarily via legacy computer and Intranet-type systems that require multiple log-ins and restrict users or network sharing in order to meet legal privacy restrictions. Both systems are largely automated and rife with inaccuracies. While DHS, with the help of a rotating cast of contractors, is attempting to fine-tune and merge both kinds of systems, it has not yet succeeded.

Constantly Expanding "Data Pool", Government Records

We propose that before this window closes further, it is both necessary and possible to dismantle data criminalization as a key step toward migrant justice and prison abolition. First, we must understand criminal legal and DHS databases.

In the following sections, we introduce a couple dozen major databases and data systems out of the more than 900 used by the Department of Homeland Security. We zoom in on two key processes that illustrate data criminalization in action: police encounters and travel surveillance. We look beyond DHS’ sub-agency, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), because Border Patrol and bureaucracies like the State Department and Citizenship and Immigration Services that regulate and administrate identity, state-sanctioned travel, work and school visas as well as naturalization play key roles in border securitization and racial ordering. We name the historical antecedents of today’s commercial data market — trans-Atlantic slavery, imperialism and settler-colonial theft — in order to understand how state violence imbues all existing technologies of biometric identification, location-stalking and behavior prediction. Finally, we propose that paths to abolition will necessarily oppose both the free market as well as state power, rethink strategies that valorize recognition or legitimacy conferred by the law, and jettison demands for individual redress on the grounds of private ownership to instead assert collective self-determination and self-governance of one’s own data, and a communization of knowledge and free exchange of information for all.

- 1 a McKenzie Funk, “How ICE Picks Its Targets in the Surveillance Age,” The New York Times, October 2, 2019, sec. Magazine, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/02/magazine/ice-surveillance-deportatio….

- 2 a Adam Liptak, “Supreme Court Limits Suit on False Terrorism Ties on Credit Reports,” The New York Times, June 25, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/25/us/supreme-court-credit-reports-terr….

- 3 a 0%20OperaNCIC 2000 Operating Manual,15, https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2019/01/16/NCIC%20200ting%20Manual….

- 4 a Eliana Phelps, “Immigration Arrests at Airport Terminals,” The Law Offices of Eliana Phelps: Immigration and Family Law Attorneys, https://phelpsattorneys.com/immigration-arrests-at-airport-terminals/.

- 5 a Randolph D. Alles, Comprehensive Strategy for Overstay Enforcement and Deterrence Fiscal Year 2018 Report to Congress, 2020, ii, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/ice_-_comprehensiv….

- 6 a Immigrant Defense Project, Denied, Disappeared, and Deported: The Toll of ICE Operations at New York’s Courts in 2019, January 2020, https://www.immigrantdefenseproject.org/wp-content/uploads/Denied-Disap….

- 7 a Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, “About the Data - ICE Detainers,” 2020. https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/detain/about_data.html.

- 8 a Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, “Removal Orders Granted by Immigration Judges as of May 2021,” 2021. https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/court_backlog/apprep_removal….

- 9 a César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández, “Creating Crimmigration, 2013 Brigham Young University Law Review 1457, February 11, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2393662

- 10 a Legacy systems in computing include outdated, obsolete and discontinued systems, program languages or application software that have been replaced by upgraded versions.

- 11 a U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Department of Homeland Security Artificial Intelligence Strategy, Department of Homeland Security, December 3, 2020, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/dhs_ai_strategy.pdf.

- 12 a Declaration of Roxana Bacon at ¶ 11, Gonzalez v. Immigr. & Customs Enf't, 416 F. Supp. 3d 995 (C.D. Cal. 2019) (No. 2:12-cv-09012-AB-FFM), ECF No. 287.

- 13 a Salvador Hernandez, “A Database Of Gang Members In California Included 42 Babies,” BuzzFeed News, August 12, 2016. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/salvadorhernandez/database-of-gang….

- 14 a Colin Daileda, “The U.S. Will Start Collecting Social and Search Data on Every Immigrant Soon,” Mashable, June 10, 2021, https://mashable.com/article/us-government-social-media-data-immigrants.

- 15 a U.S. Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General, DHS Tracking of Visa Overstays is Hindered by Insufficient Technology, 2017, 7–12. https://www.oig.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/assets/2017/OIG-17-56-May17….

- 16 a U.S. Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General, An Assessment of the Proposal to Merge Customs and Border Protection with Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2005, 6–7. https://www.oig.dhs.gov/assets/Mgmt/OIG_06-04_Nov05.pdf.

- 17 a Robert C. King III, “The Department of Homeland Security’s Pursuit of Data-Driven Decision Making,” 2015, 55. https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=790344.

- 18 a Office of Inspector General, An Assessment of the Proposal to Merge Customs and Border Protection with Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2005. https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/library/P954.pdf.

- 19 a Office of Inspector General and U.S. Department of Homeland Security, “ICE Deportation Operations,” April 13, 2017, 5. https://www.oig.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/assets/2017/OIG-17-51-Apr17….

- 20 a Gonzalez, 975 F.3d at 800.

- 21 a Susan Long, Puck Lo Interview with Susan Long, April 5, 2021.

- 22 a B. I. Incorporated, BI SmartLINK: Client Smartphone Monitoring App, 2021. https://vimeo.com/539164848.

- 23 a Edward Hasbrouck, Puck Lo Interview with Edward Hasbrouck, Phone, April 2, 2021.

- 24 a Sara DeStefano, “Unshackling the Due Process Rights of Asylum-Seekers,” Virginia Law Review 105, no. 8, December 29, 2019. https://www.virginialawreview.org/articles/unshackling-due-process-righ….

- 25 a U.S. Department of Homeland Security, “Detention Management,” 2021. https://www.ice.gov/detain/detention-management.

- 26 a U.S. DHS, “Detention Management.”

- 27 a Audrey Singer, “Immigration: Alternatives to Detention (ATD) Programs,” July 8, 2019. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/homesec/R45804.pdf.

- 28 a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, “Detention Management,” 2021. https://www.ice.gov/detain/detention-management.

- 29 a Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, “Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Now Monitors About 118,000 Immigrants Through Its Alternatives to Detention Program,” September 2, 2021. https://trac.syr.edu/whatsnew/email.210902.html.

- 30 a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, “Detention FY 2021 YTD, Alternatives to Detention FY 2021 YTD and Facilities FY 2021 YTD,” 2021, https://www.ice.gov/doclib/detention/FY21_detentionStats08242021.xlsx.

- 31 a Maye Primera and Mauricio Rodríguez-Pons, “Months After ICE Raids, an Impoverished Mississippi Community Is Still Reeling,” The Intercept, October 13, 2019. https://theintercept.com/2019/10/13/ice-raids-mississippi-workers/.

- 32 a U.S. Department of Homeland Security, “Detention Management,” 2021. https://www.ice.gov/doclib/detention/atdInfographic.pdf.

- 33 a Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/quickfacts/

- 34 a U.S. Department of Homeland Security, “Privacy Impact Assessment for the CBP Portal (E3) to EID/IDENT,” August 10, 2020, 5, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/privacy-pia-cbp012….

- 35 a DHS, “Privacy Impact Assessment for the CBP Portal (E3) to EID/IDENT,” August 10, 2020, 5, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/privacy-pia-cbp012….

- 36 a U.S. Department of Homeland Security, “Privacy Impact Assessment for the CBP ONE™ Mobile Application,” February 19, 2021, www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/privacy-pia-cbp068-cbpmobi….

- 37 a Bryan Baker, “Estimates of the Lawful Permanent Resident Population in the United States and the Subpopulation Eligible to Naturalize: 2015-2019,” U.S. Department of Homeland Security Office of Immigration Statistics, September 2019, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/immigration-statis….

- 38 a Jeanne Batalova, Mary Hanna, and Christopher Levesque, “Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States,” Migration Policy Institute, February 11, 2021, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/frequently-requested-statistics….

- 39 a Stuart Thompson and Charlie Warzel, “One Nation, Tracked,” New York Times, December 19, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/12/19/opinion/location-trackin….

- 40 a Sara Morrison, “The Hidden Trackers in Your Phone, Explained,” Vox, July 8, 2020. https://www.vox.com/recode/2020/7/8/21311533/sdks-tracking-data-location.

- 41 a Thompson and Warzel, “How to Track President Trump,” New York Times, December 20, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/12/20/opinion/location-data-na….

- 42 a Brooke Auxier et al., “Americans and Privacy: Concerned, Confused and Feeling Lack of Control Over Their Personal Information,” Pew Research Center, August 17, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/11/15/americans-and-privacy-c….

- 43 a Shoshana Zuboff, “You Are Now Remotely Controlled,” New York Times, January 24, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/24/opinion/sunday/surveillance-capitali….

- 44 a Noah Kulwin, “Shoshana Zuboff Talks Surveillance Capitalism's Threat to Democracy,” Intelligencer, February 25, 2019, https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2019/02/shoshana-zuboff-q-and-a-the-age….

- 45 a Kulwin, “Shoshana Zuboff.”

- 46 a Yasha Levine, Surveillance Valley: The Secret Military History of the Internet (2018).

- 47 a Johana Bhuiyan and Sam Levin, “Revealed: the software that studies your Facebook friends to predict who may commit a crime, The Guardian, November 17, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/nov/17/police-surveillance-tec….

- 48 a Sarah Brayne, “Big Data Surveillance: The Case of Policing,” American Sociological Review 82:5, August 29, 2017, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122417725865.

- 49 a Rani Molla, “Forget Warrants, ICE Has Been Using Cellphone Marketing Data to Track People at the Border,” Vox, February 7, 2020, https://www.vox.com/recode/2020/2/7/21127911/ice-border-cellphone-data-….

- 50 a Blake Ellis, “The banks' billion-dollar idea,” CNN Money, July 8, 2011, https://money.cnn.com/2011/07/06/pf/banks_sell_shopping_data/index.htm.

- 51 a In December 2021, after being pressured by Mijente’s NoTechForICE campaign, Just Futures Law, and an Oregon state senator, the National Consumer Telecom & Utilities Exchange agreed to stop selling new utility bill information, home addresses, Social Security numbers and other personal data to Equifax, a credit bureau. Equifax has been selling this information, culled from some 171 million utility and telecom subscribers, to data aggregators like Thomson Reuters, who contract with ICE. Unfortunately, customer data from before October 2021 continues to be retained and can be resold, and credit agencies like Equifax, Experian and TransUnion continue to receive so-called “credit header” data from banks. Ron Wyden, “Sen. Wyden letter to CFPB on sale of Americans' utility data,” The Washington Post, December 8, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/context/sen-wyden-letter-to-cfpb-on-sale….

- 52 a Max Rivlin-Nadler, “How ICE Uses Social Media to Surveil and Arrest Immigrants,” The Intercept, December 22, 2019, https://theintercept.com/2019/12/22/ice-social-media-surveillance/; see also Drew Harwell, “ICE investigators used a private utility database covering millions to pursue immigration violations,” Washington Post, February 26, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2021/02/26/ice-private-utilit…; Benjamin Hayes, “U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Use of Automated License Plate Reader Databases,” 33 Georgetown Immig. L.J. 145, 2018, https://www.law.georgetown.edu/immigration-law-journal/wp-content/uploa….

- 53 a “The Stanford Open Policing Project,” accessed April 19, 2021, https://openpolicing.stanford.edu/.

- 54 a Peter Eisler et al., “Why 4,998 Died in U.S. Jails before Their Day in Court,” Reuters, October 16, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/usa-jails-deaths/.

- 55 a Community Justice Exchange, An Organizer’s Guide to Confronting Pretrial Risk Assessment Tools in Decarceration Campaigns, December 2019, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e1f966c45f53f254011b45a/t/5e35a….

- 56 a Derek Gilna, “Criminal Background Checks Criticized for Incorrect Data, Racial Discrimination,” Prison Legal News, February 15, 2014, https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2014/feb/15/criminal-background-ch….