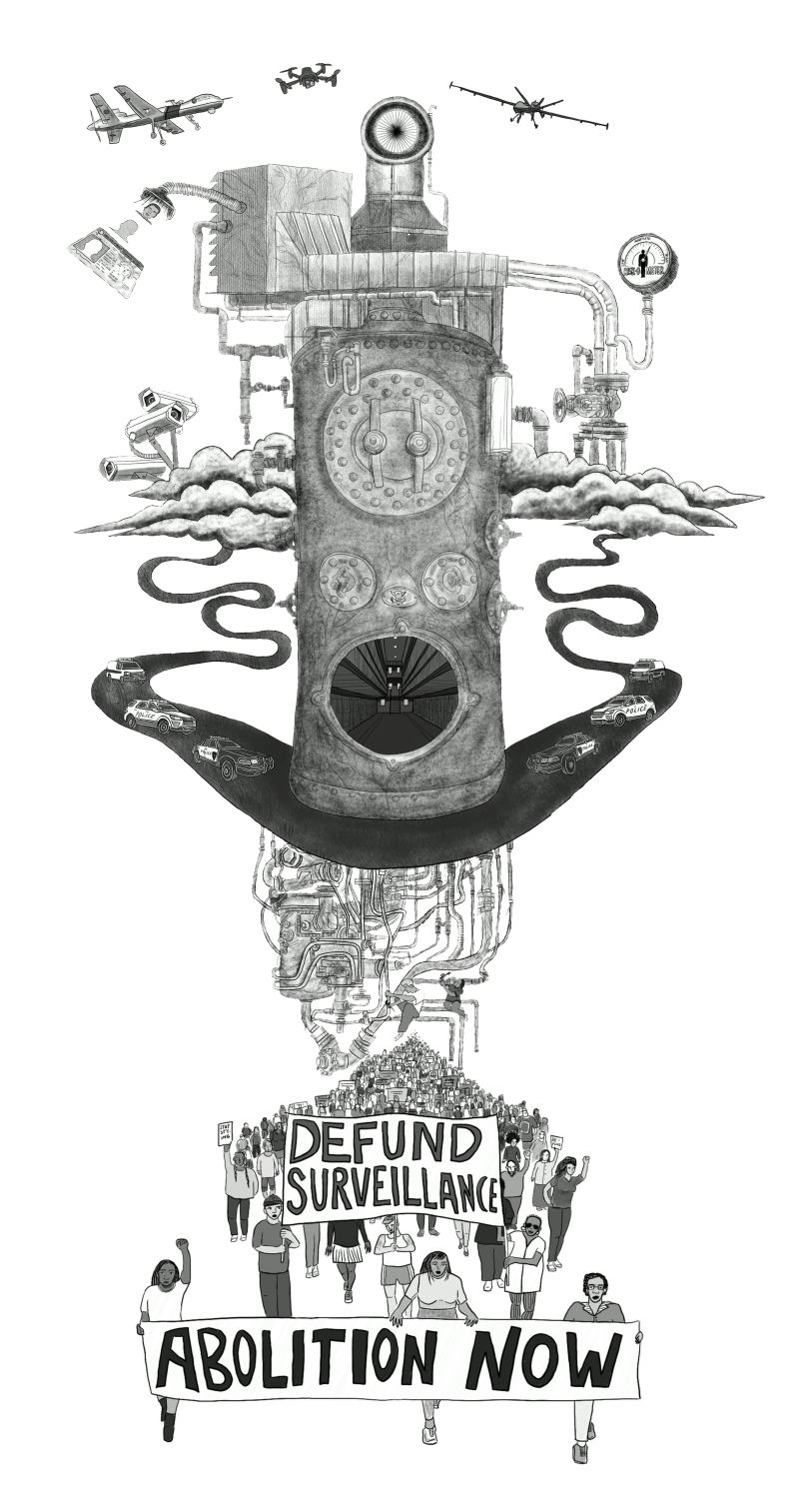

For many of us today, “surveillance” may seem baked into our daily lives. It may seem impossible, in the post-9/11 world, to stay unwatched, or leave no trace. Whether it is through video cameras mounted in public places, or our use of cell phones and Internet searches, it seems like almost everything we do can be tracked by anyone with the right tools.

To attempt to resist surveillance may seem anachronistic at best, and futile and paranoid at worst.

“Data” and “data collection” in today’s world may seem to be a given. Many of us believe in the inherent validity of data collection and analysis as features of our modern reality that can improve our lives. We may associate “data” with things that are scientific, measurable, and objective.

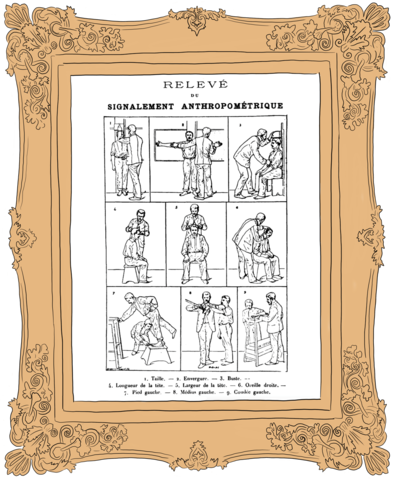

But data collection methodologies and categories as they exist today inherit and wield the weight of centuries of state strategies and justification for identifying, managing and controlling populations that could threaten ruling class interests. There is nothing neutral about data, and nothing passive about surveillance. Surveillance uses data to sort us categorically and, in the words of theorist Simone Browne, “weigh some of us down” by differentially exposing some of us to state violence, even as it disguises and naturalizes the process of doing so.

There is nothing neutral about data, and nothing passive about surveillance.

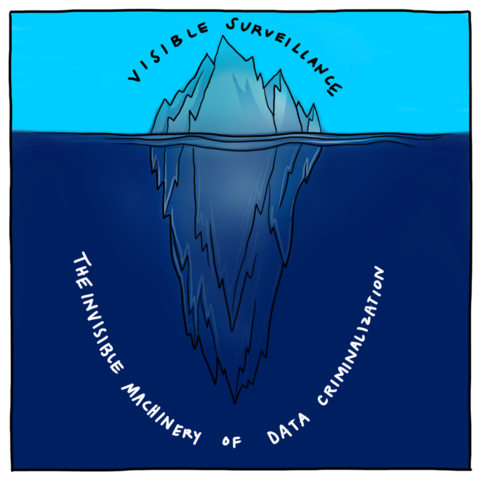

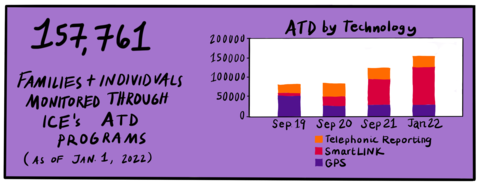

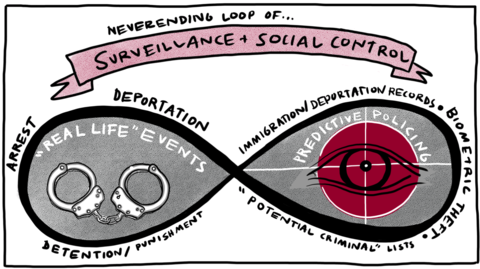

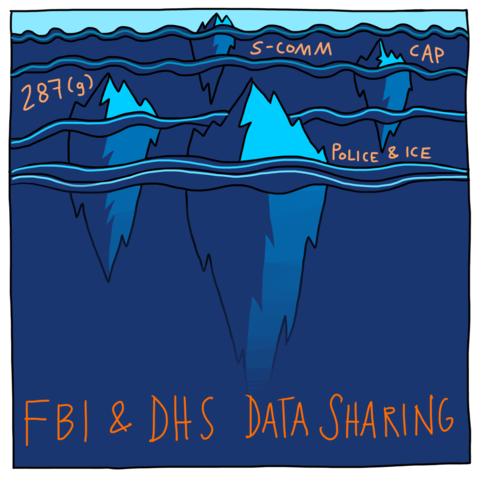

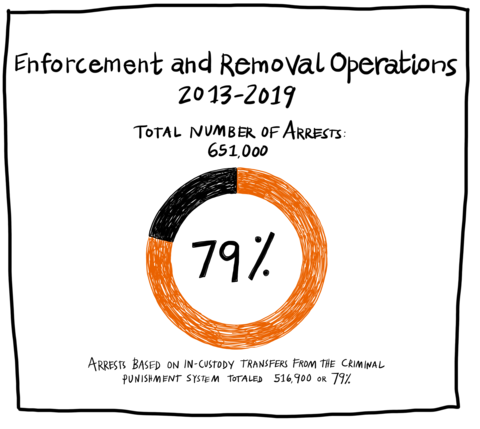

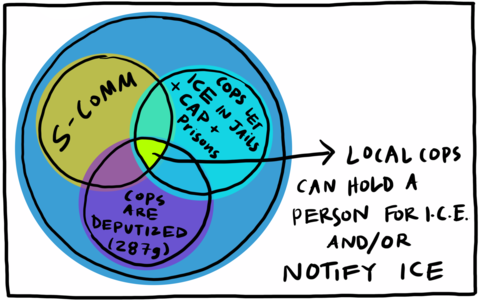

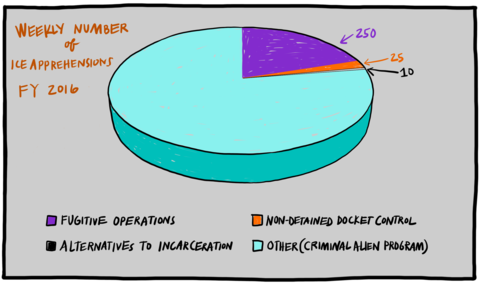

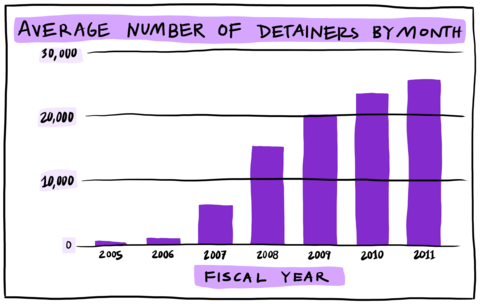

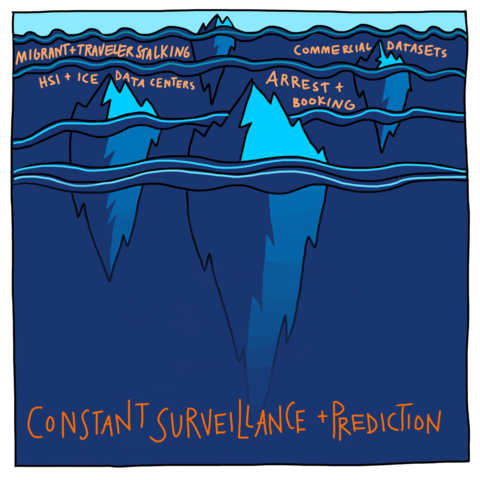

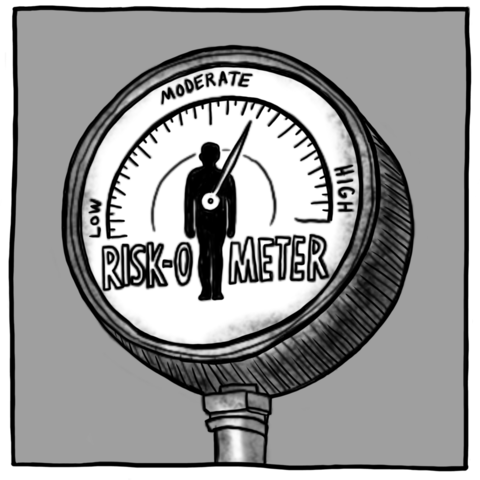

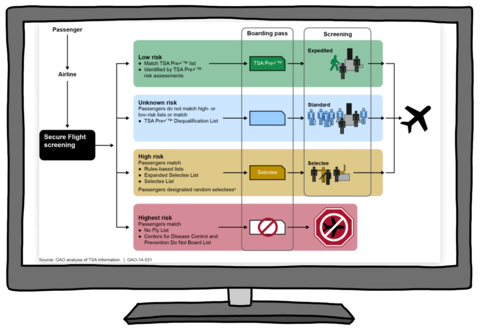

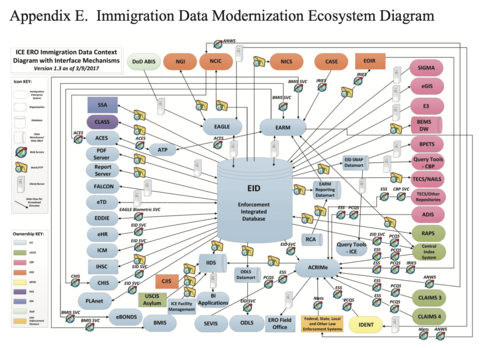

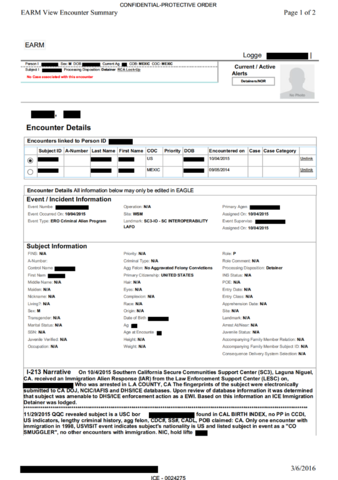

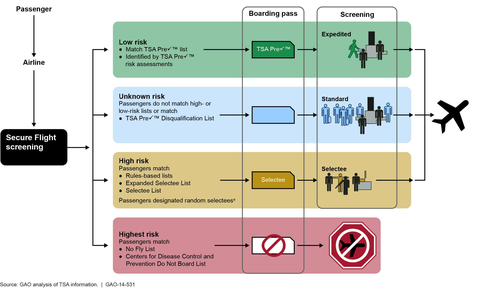

Migrants are especially weighed down. Migrants exist precariously in the modern nation-state and globalized neoliberal economy, often producing wealth for multiple countries while being denied legal rights and subjected to continuous, enhanced scrutiny, dislocation and punishment. While many of the systems that mark and maintain migrant vulnerability are not visible, by examining technical processes that target and “vet” migrants we can identify a key feature of law enforcement-oriented “data-driven technologies” today: They are engineered to guarantee that a person who was criminalized in the past or present will, by design, continue to be criminalized in the future, whether or not they break any laws. Since a key feature of our legal structure is to separate out and exclude people, law enforcement oriented data-driven technologies are designed to ensure that targeted people fit into criminalized categories that justify exclusion under and beyond the law. For instance, migrant surveillance is automated so that any person who was born outside the US always remains suspicious.

Since a key feature of our legal structure is to separate out and exclude people, law enforcement oriented data-driven technologies are designed to ensure that targeted people fit into criminalized categories that justify exclusion under and beyond the law.

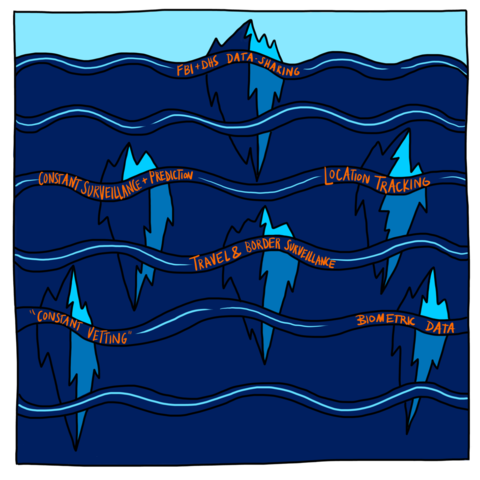

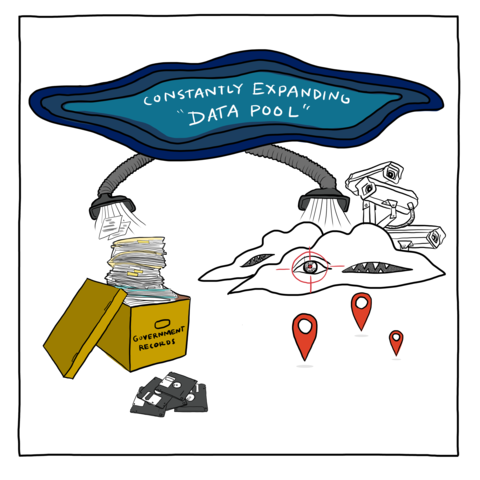

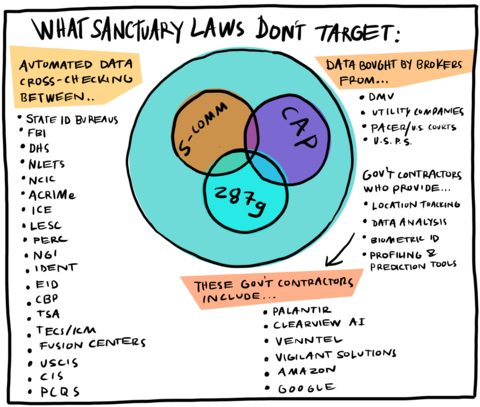

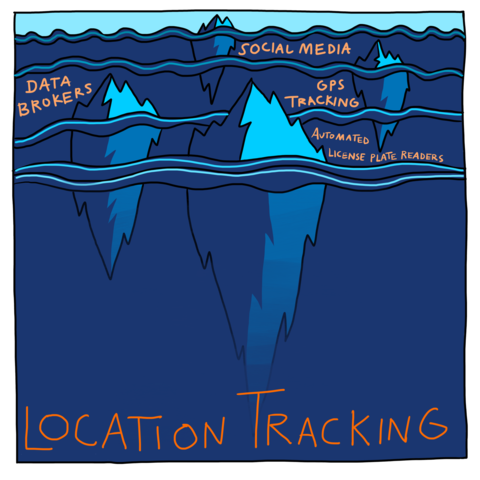

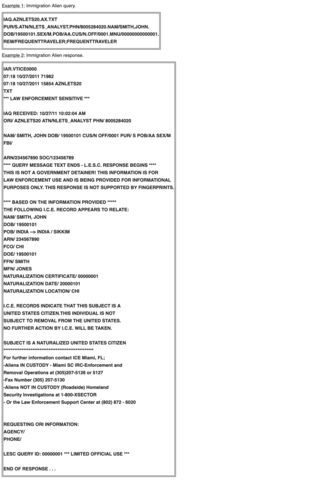

Therefore, exemption from enforcement (arrest, incarceration and/ or deportation) is conferred only temporarily, moment-by-moment, as a person’s extra-legal “permanent record” (which includes arrest data that did not result in conviction, freehand observational notes from border crossings, past travel itineraries collected by commercial airlines, and unproven accusations by police and travel authorities of membership in gangs or terrorist groups) is cross-referenced against dozens of (often inaccurate and outdated) government- and privately-run criminal legal and commercial datasets and “risk” prediction software.

Criminalization is the process and practice that justifies such cataloguing and control of targeted populations, individually and categorically.

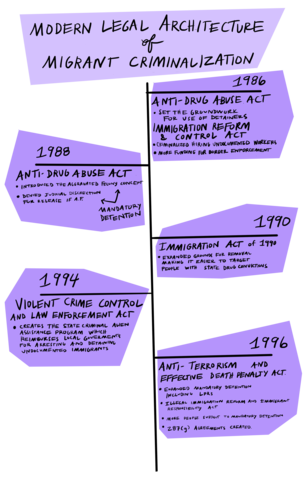

Criminalization is the process and practice that justifies such cataloguing and control of targeted populations, individually and categorically. Through criminalization, migrants are weighed down unevenly by what sociologist Ana Muñiz calls “securitized immigration control,” which characterizes and punishes Muslims and Middle Eastern migrants as terrorists, and Central American and Mexican migrants as gang members, criminals and drug traffickers.

The criminalization of migrants, using data, is the focus of our project.

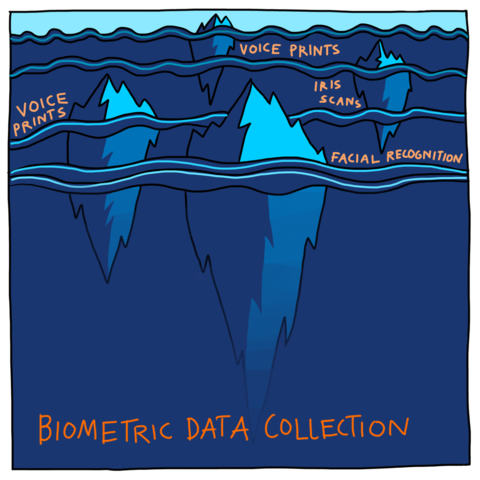

Criminalization legitimates the formal exclusion of a person from full legal rights, and exposure to premature death and foreshortened life chances. The state uses legal doctrine and pseudoscientific criminological concepts to create and marshal supposedly objective data to prove a person’s criminality and argue for intervention and correction, often in the forms of diminished legal status and punishment. Criminalizing data is often created by surveillance. We define surveillance as the non-consensual observation of individuals and communities by state, corporate or academic entities who have power to make meaning from, exert control over, exploit or otherwise profit from an observed population. Surveillance is active intervention in the form of behavior prediction for modification; it is real-time social control.

Surveillance is active intervention in the form of behavior prediction for modification; it is real-time social control.

For too long, we have characterized the expansive nature of information-sharing, biometric collection, technologies used by law enforcement, and commercial partnerships with law enforcement as a problem of individual tech vendors driven by profit-seeking. Within the migrant justice movement, we have focused on individual kinds of technologies, programs and companies without contesting the fact that the very grounds on which these practices are premised are illegitimate and derive from centuries-old racist justifications for land theft and trans-Atlantic enslavement. Instead, we have often uncritically adopted corrective solutions for modern-day surveillance that come from pro-Constitutional “privacy” rights perspectives, which fixate on procedural protections, oversight of new technologies, the theatrics of “consent,” and are grounded in a conceptual and legal framework derived from white property rights that fail to protect those of us who are criminalized, non-citizens or otherwise excluded from legal privileges.

Today, collectively, many of us are turning a corner. As concepts like surveillance capitalism begin to permeate the mainstream and news articles reveal how smartphone apps and utility providers sell our personal info to commercial data brokers and ICE, we can tap into a growing collective disgust of data theft.

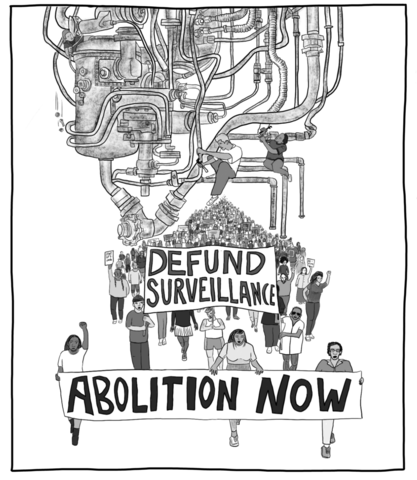

The time is ripe for a new mass movement to dismantle criminalization on the road to abolition.