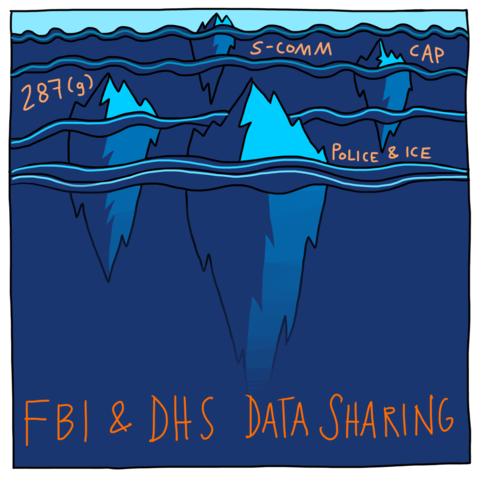

FBI & DHS Data Sharing, S-Comm, 287(g), CAP, Police and ICE

In the following sections, we examine how data criminalization operates within:

- Police encounters and profiling

- Automated data-sharing systems used by law enforcement agencies

- Surveillance capitalism: the expanding market of data brokers, cell phone apps, social media and digital stalking

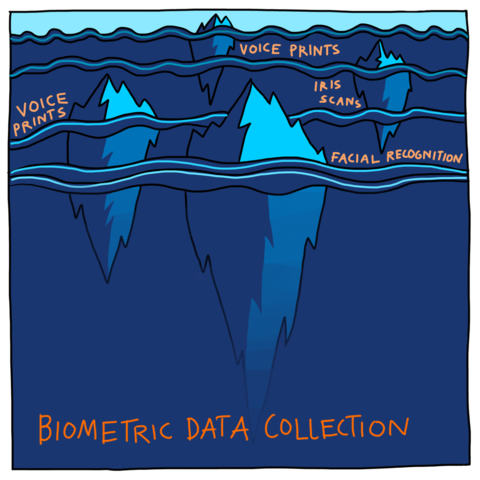

- Biometric technologies and covert identification practices

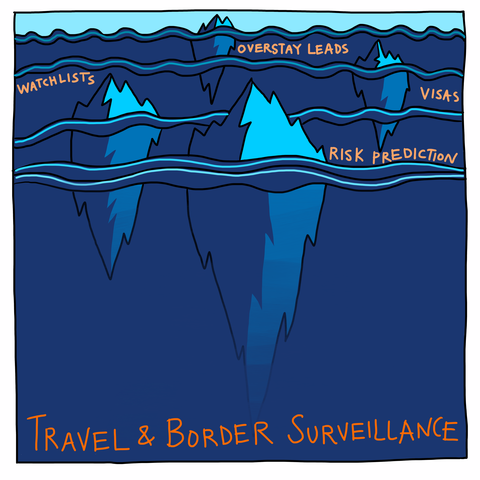

- Traveler surveillance and securitization

- Bureaucratic pathways to visas and naturalization

For this report, we do not aim to provide a complete taxonomy of all government and commercial databases used to criminalize, but instead ask how the tangled and blurry morass that we can discern might indicate how a larger machinery operates.

Constructing crimmigration

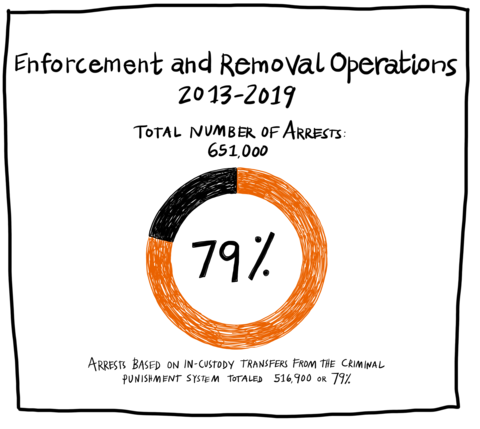

Collaborations and data-sharing between law enforcement and ICE have been the most efficient way to criminalize and deport record numbers of immigrants from the US. The majority of ICE arrests are based on hand-offs from jails and prisons directly to ICE. A 2020 DHS Office of the General Inspector audit analyzed Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) data from 2013-2019 and found that “516,900, or 79 percent of its 651,000 total arrests, were based on in-custody transfers from the criminal-justice system.”Note en bas de page 1

Image Source Note en bas de page 2

Enforcement and Removal Operations 2013-2019, Total Number of Arrests 651,000, Arrests based on in-custody transfers from the criminal punishment system totaled 516,900 or 79%

Digitization and centralization of government databases began as early as 1967 with FBI records.Note en bas de page 3 However, the digitization of migrant records came much later. It was not until 2008 that fingerprints accompanying applications for immigration “benefits” like travel visas and naturalization were uploaded, and 2010 when ICE investigators began consistently uploading fingerprints taken from people during law enforcement encounters.Note en bas de page 4

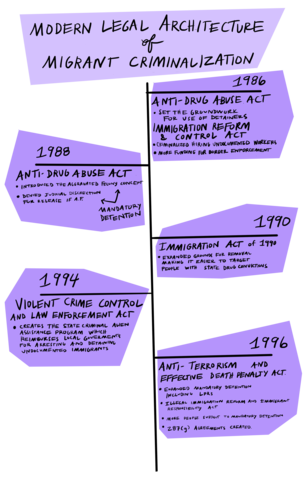

The legal architecture of modern US immigrant criminalization is less than forty years old.

Many key laws have roots as recent as the 1980s, when the Cold War and the racialized War on Drugs collided. In 1986, the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) criminalized hiring undocumented workers for the first time in US history, and increased resources for the INS to patrol the border.Note en bas de page 5 IRCA also mandated the US Attorney General to deport noncitizens convicted of “removable offenses” as quickly as possible. This began the practice of targeting immigrants convicted of crimes and expanded the mechanisms for policing immigrants.

Source Note en bas de page 6

Modern Legal Architecture of Migrant Criminalization. 1986: Anti-Drug Abuse Act: Set the groundwork for use of detainers. Immigration Reform and Contral Act: Criminalized hiring undocumented workers, More funding for border enforcement. 1988: Anti-Drug Abuse Act: Introduced the aggravated felony concept, denied judicial discrection for release. If Aggravated Felony, Mandatory Detention. 1990: Immigraton Act of 1990: Expanded grounds for removal making it easier to target people for state drug convictions. 1994: Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act: Creates the state criminal aliens assistance program which reimburses local governments for arresting and detaining undocumented immigrants.1996: Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act: Expanded mandatory detention including LPRs, Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, More people subject to Mandatory Detention, 287(g) Agreements Created.

The Clinton administration continued and expanded those practices, passing the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, or AEDPA, which created and expanded the grounds for mandatory immigrant detention and deportation, including for long-term legal residents. It was the first US law to formally authorize fast-track deportation procedures, a modified form of which is widely used today.Note en bas de page 7

Additionally, the Clinton administration passed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigration Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) in 1996, which conflated immigration and criminality.Note en bas de page 8 IIRIRA is a keystone of our current immigration policy. It:

- enabled the creation of the 287(g) program, which allowed DHS to enter into agreements with local law enforcement to perform certain functions of immigration agents;

- expanded the list of convictions that trigger “mandatory” detention; and

- increased the number of convictions that trigger deportation by further expanding a category applicable only to immigrants that was created by the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988: “aggravated felonies.”Note en bas de page 9

Congress determines which offenses qualify as aggravated felonies (not all aggravated felonies are felonies), and an aggravated felony conviction precludes access to relief like asylum and increases vulnerability to deportation.

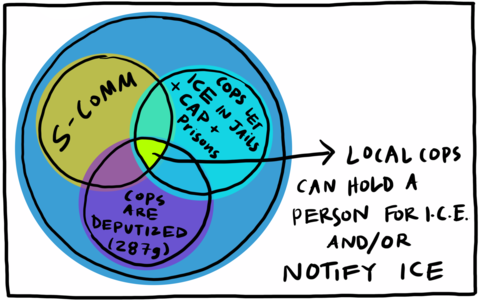

Police + ICE collaboration

In the following section, we look at three notable police-ICE partnerships that institutionalized data criminalization of migrants and non-citizens within non-immigration law enforcement protocols.Note en bas de page 10 As we will see, systemic information-sharing at the data network level nullifies many of the sanctuary agreements that are in place today.

Formal FBI and DHS database integration is even newer than the crimmigration laws named above, dating back to around 1998. It accelerated following the 2001 Patriot Act, when Congress mandated the creation of an electronic system to share law enforcement and intelligence information to confirm the identities of people applying for United States visas.Note en bas de page 11 At the same time, Congress restructured federal law enforcement laws to conflate “national security,” “crime control,” and “immigration control.”Note en bas de page 12 Just one year later, in 2002, Congress created DHS and granted it immediate access to information in federal law enforcement agencies’ databases, sealing the deal for an interlocking web of automated database sharing.

Various programs since the 1980s had already given immigration authorities access to police data, jails and prisons. These programs often do not have clear beginning and end dates. There are implementation differences based on region, and there are overlaps and inconsistencies. Furthermore, in response to public pressure opposing formal law enforcement collaborations with ICE, the agency continued its information-sharing collaborations with local and state law enforcement — but often under the radar. Today, much data-sharing and immigration status-querying is built into the computer systems used by law enforcement to perform routine functions (like uploading someone’s fingerprints). Under the current automated systems, every single person who was born outside of the US — or whose birthplace is unknown to US government databases — is automatically scrutinized for deportation if they are arrested and booked for anything, regardless of the charge and whether it is ultimately dismissed.Note en bas de page 13

S-COMM, Cops Let ICE in jails and CAP and Prisons, Cops are Deputized 287(g), Local Cops can hold a person for ICE and/or Notify ICE

Criminal Alien Program

The Criminal Alien Program (CAP) has been around in one form or another since a 1986 law decreed that people convicted of certain crimes should be an enforcement priority. CAP has been more aggressive in some states than others. “The unevenness in the program certainly implies that the preferences of state and local law enforcement officers (as well as the preferences of ICE agents in one region or another) played a role,” a Vox article stated.Note en bas de page 14 Today, CAP is an umbrella program that includes a variety of local law enforcement and ICE partnerships with names like VCAS, LEAR, REPAT, DEPORT, JCART, which use tactics ranging from in-person “jail checks” to automated biometric database-sharing.Note en bas de page 15

CAP began as mostly low-tech, voluntary collaborations between local law enforcement and immigration enforcement. Under CAP, jails and prisons often shared booking records with immigration agents and/or allowed immigration agents in-person access to interrogate incarcerated people ICE suspected it could deport — regardless of whether the booked person could eventually be charged or convicted.Note en bas de page 16 CAP allows local cops to funnel people directly into ICE’s custody, and allows ICE to use the criminalization process as a tool to facilitate mass deportations. CAP absolutely is premised on racial and national origin profiling and targeting: If you are a “suspected noncitizen,” that is enough to qualify you for a CAP screening and ICE interrogation in jail or prison.Note en bas de page 17 A 2013 American Immigration Council report found that CAP screens “all self-proclaimed foreign-born nationals found within Bureau of Prisons (BOP) facilities and all state correctional institutions.”Note en bas de page 18

Despite its name, CAP programs were used to deport more than 22,000 immigrants without criminal records between FY 2013 and FY 2016.Note en bas de page 19

CAP was in place long before S-Comm was piloted in 2008 (more on S-Comm below). It operates out of all ICE field offices, in all state and federal prisons, and many local jails.Note en bas de page 20 It has blended seamlessly with S-Comm machinery and processes, as ICE makes use of many of the same automated database checks set in motion by law enforcement booking and heavily relies on cooperation from jails and prisons to honor detainers and requests for notification of release. During the Obama era, CAP was the primary mechanism through which ICE deported people from the US interior.Note en bas de page 21 Vox reported that CAP was responsible for between two-thirds and three-quarters of deportations during the Obama era of the early 2010s.Note en bas de page 22 TRAC at Syracuse University concluded similarly for FY 2016, based on analysis of case-by-case records on both apprehensions and removals data obtained from ICE in response to hundreds of Freedom of Information Act requests, appeals, and a successful lawsuit.Note en bas de page 23

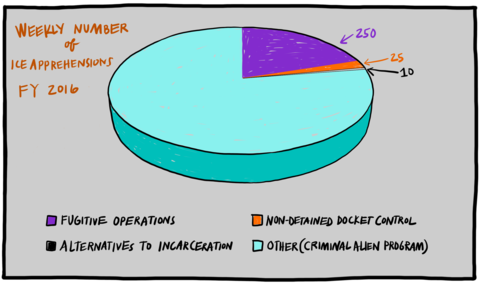

Source Note en bas de page 24

Weekly Number of Ice Apprehensions FY 2016, Fugitive Operations, Alternatives to Incarceration, Non-Detained Docket Control, Other (Criminal Alien Program)

Although CAP is still known by many as a “jail status screening” program, both CAP and S-Comm use automated systems (detailed below) that attempt to match to FBI files and immigration records biographical and biometric information taken from a person by a cop during booking. Historically, “biometrics” has generally meant fingerprints; today, ICE and the FBI are outfitted with facial recognition software and readily available photo data from state driver’s licenses, visa and naturalization records as well as photos scraped from the Internet and social media.

287(g) agreements

Section 287(g) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) allows DHS to deputize state and local police to carry out federal immigration enforcement through interrogations and arrests, or following resolution of local, state, or federal charges. These partnerships today take two main forms: the “jail enforcement model,” which authorizes local police to issue immigration detainers, or the “warrant service officer model,” which ask jails or prisons to notify ICE, or hold a person for ICE, if a person is suspected of being deportable.Note en bas de page 25 287(g) partnerships are voluntary and formalized through MOU agreements made between state or local law enforcement with federal immigration authorities.Note en bas de page 26

The Trump administration dramatically increased the number of 287(g) agreements — from 34 at the end of 2016 to 151 as of November 2020. However, despite the increase in 287(g) agreements, it is difficult to calculate if deportations increased as a result. ICE claims that it does not break out 287(g) data to count deportations, and instead issues monthly reports of “encounters” that only include “a sampling” of people identified under the 287(g) program.Note en bas de page 27

Secure Communities (S-Comm)

S-Comm was piloted by DHS in 2008. It formalized the now-ubiquitous automated process of forwarding fingerprints collected during law enforcement booking to check against immigration and travel databases for potential deportability.

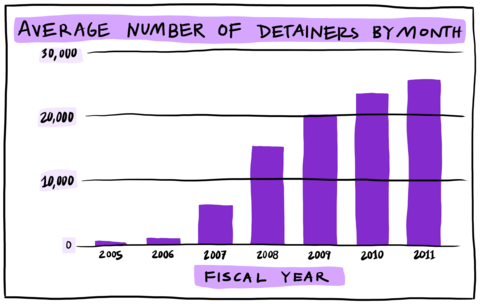

Automating database checks had immediate and dramatic consequences. One product of ICE automation is the detainer (detailed below) — which has taken either the form of ICE requesting that a jail or prison “hold” a person who could be released, or a request from ICE for “notification of release” of a person whom ICE thinks might be deportable. In FY 2005, ICE issued roughly 600 detainers based on automated fingerprint matches per month — but by the end of FY 2011, monthly detainers exceeded 26,000. Although S-Comm was voluntary at first, following opposition from advocates and community members in New York, Massachusetts, and Illinois, the federal government mandated the program.Note en bas de page 28 By January 22, 2013, S-Comm database sharing had been fully implemented in all 3,181 jurisdictions within 50 states, the District of Columbia, and five US territories.

SourceNote en bas de page 29

Average Number of Detainers by Month, Fiscal Year

S-Comm generated much public backlash, and various communities have pressured their jurisdictions and Sheriffs to refuse to cooperate with ICE detainers. TRAC reported that “law enforcement agencies with the most recent recorded refusals were concentrated in New York and California,” and two out of three detainer requests addressed to Queens and Brooklyn Central Booking were recorded as refused.Note en bas de page 30 Santa Clara County in California refused to honor detainers over 90 percent of the time.

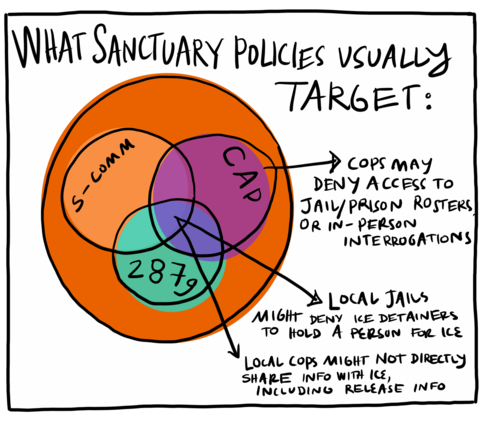

S-COMM, CAP, 287g, WHAT SANCTUARY POLICIES USUALLY TARGET: Cops may deny access to jail/prison rosters or in-person interrogations, Local jails might deny ICE detainers to hold a person for ICE, Local cops might not directly share info with ICE, including release info

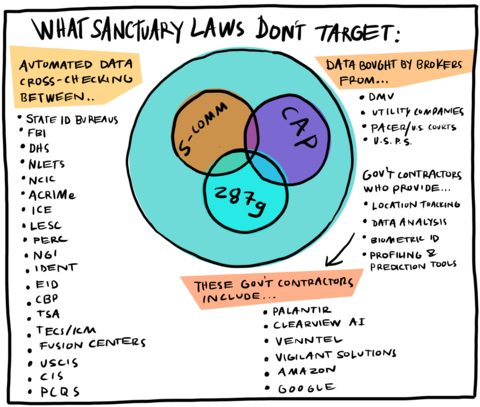

WHAT SANCTUARY LAWS DONT TARGET: AUTOMATED CROSS CHECKING BETWEEN... State ID Bureaus, FBI, DHS, NLETS, NCIC, ACRIMe, ICE, LESC, PERC, NGI, IDENT, EID, CBP, TSA, TECS/ICM, FUSION CENTERS, USCIS, CIS, PCQS; DATA BOUGHT BY BROKERS: DMV, UTILITY COMPANIES, PACERS, U.S. COURTS, USPS; GOV'T CONTRACTORS WHO PROVIDE... Location Tracking, Data Analysis, Biometric ID, Profiling and Prediction Tools, THESE GOV'T CONTRACTORS INCLUDE... PALANTIR, CLEARVIEW AI, VENNTEL, VIGILANT SOLUTIONS, AMAZON, GOOGLE

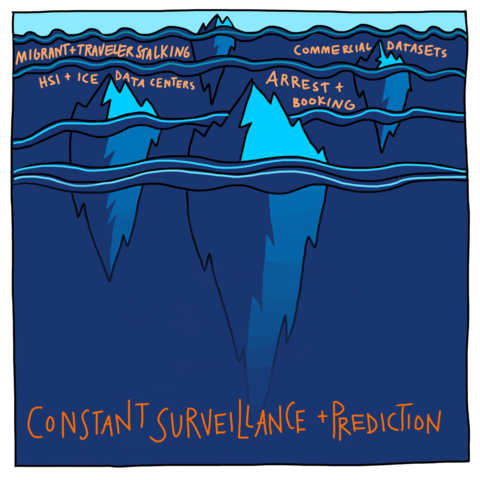

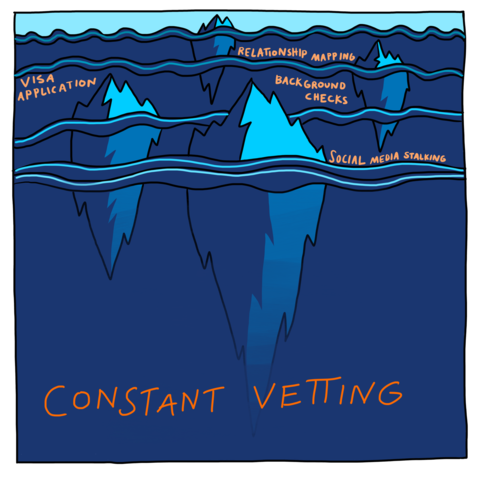

Laudable though these victories have been for organizers, especially at the local level, it is important to keep in mind that detainers are just the tips of those icebergs — and if a person is not directly transferred to ICE custody from local law enforcement, there are still a number of ways that ICE is able to locate and control a person who is marked by criminalizing databases.

Automated processes of data criminalization

Constant Surveillance and Prediction, "migrant and traveler stalking," "commercial datasets," "arrest + booking," and "HSI and ICE data centers"

How can we dismantle the entire system of data criminalization, which is fully automated at the database and computer level? Here, we take an in-depth look at two of these processes and data systems.

- Arrest and booking: Database cross-checking with some DHS records became standard procedure in daily policing during the era of S-Comm implementation, but things didn’t stop there. Today, criminal punishment data is merged with an expanding array of DHS datasets and commercially sold cell phone app, location and identification data for prediction and profiling purposes. Below, we detail a shortened version of this process, step-by-step.

- Travel surveillance and criminalization: Well before S-Comm, and even before September 11, 2001, airline surveillance and Internet purchase spying was already a norm. Since 9/11, as we will see, the state has largely replaced its former “blacklist” model with algorithmic continuous trolling, creating and using AI to process massive amounts of data and to selectively target any chosen population. Section 7 describes historical and cutting-edge tools and techniques used to covertly identify people in public spaces as well as carceral ones, and match them to multiple private and public datasets in order to evaluate them for the ambiguous quality of “risk.”

Detainers: criminalizing potential

For those of us who are in contact with the immigration system, a detainerNote en bas de page 31 or immigration hold (a version of Form I-247Note en bas de page 32 ) may be the first artifact we encounter in ICE’s data criminalization process that follows a police stop. Detainers are requests by ICE for law enforcement to hold someone in jail or prison for up to 48 hours past the point when they would be released from custody, or to notify ICE prior to release. Some version of an immigration detainer has been used by the precursor to ICE, the INS, since at least the 1950s.Note en bas de page 33 But it wasn’t until S-Comm’s launch in 2008 that issuance of immigration detainers skyrocketed.Note en bas de page 34 S-Comm automated the process, which, combined with the massive legal machinery of immigrant criminalization and deportation that developed over decades, created the data criminalization dragnet that is in effect today.

Detainers cast a wide net, translating ICE’s internal version of “probable cause” into an arrest and possible deportation by attempting to connect the biometric and data profile of a person to records kept by government agencies and commercial databases that show possibility of a visa overstay, entry without inspection, an open warrant, criminal conviction, previous deportation or any other factor that makes a person vulnerable to ICE arrest.Note en bas de page 35

For much of the last decade, ICE has relied heavily — ideologically and practically — on the detainer. In turn, the detainer relies on digital automated data cross-referencing. As an October 2020 Congressional Research Service report notes, “most ICE detainers are based on electronic database checks.”Note en bas de page 36

Using the detainer, ICE converts criminalized data into enforcement potential. By merging criminal and immigrant datasets, detainers purport to make real the longstanding claim that immigration is synonymous with criminality, and therefore, immigration and criminal enforcement are the same. But immigration detainers are not legally enforceable judicial warrants or official court “notices to appear;” they are just (legally questionable) requests from ICE to fellow law enforcement.Note en bas de page 37

Not just deportation, but “interoperability” and constant tracking

Detainers are not an endgame in and of themselves. They are visible iceberg tips that are part of automated processes that come downstream following multiple steps of data criminalization.

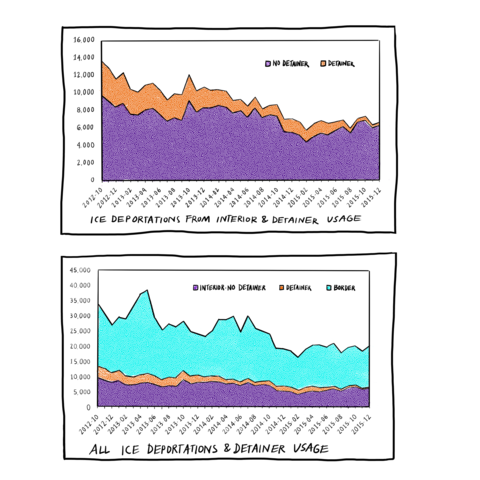

If we look at detainers alone, the story seems inconclusive. As noted earlier, in FY 2019 ICE did not take into custody up to 80 percent of the individuals for whom PERC issued immigration detainers.Note en bas de page 38 These folks may still be located by ICE at their homes or upcoming criminal court dates for interrogation and/or arrest, but if they aren’t, they may remain in limbo until a new event or encounter triggers the machinery of data criminalization once again.

Even amid peak deportations during the Obama era in 2013, S-Comm’s fingerprint match-to-deportation ratio was at its highest, yet accounted for only around a quarter (28 percent) of ICE removals from non-border areas of the US, and less than 12 percent of all ICE removals.Note en bas de page 39 Likewise, despite aggressive support for S-Comm by ICE under Trump, between 2016 and July 2017, only 2.5 to 5 percent of S-Comm deportations from the interior US were the result of detainers sent to local law enforcement agencies. TRAC noted: “When compared with ICE removals from all sources” — not just S-Comm fingerprint matches — “this component made up even a smaller proportion — less than 1 percent of all ICE removals.”Note en bas de page 40

Source Note en bas de page 41

ICE DEPORTATIONS FROM INTERIOR AND DETAINER USAGE, NO DETAINER, DETAINER, INTERIOR-NO DETAINER, DETAINER, BORDER, ALL ICE DEPORTATIONS AND DETAINER USAGE

What the data suggest then is that detainers are not particularly effective as direct pipelines for the deportation of individuals, even those made vulnerable by the criminal legal system. It seems rather that the state’s long game has been to establish a well-oiled “interoperable” machinery of databases that ensure that no matter who is in charge formally, a separate system — governed by targeting decisions, algorithms, and operating procedures — is able to expand and toggle between hidden, real-time, long-term tracking of individuals and high-profile, punitive enforcement intended to manage and criminalize communities of people based on the priorities of the moment.

It seems rather that the state’s long game has been to establish a well-oiled “interoperable” machinery of databases that ensure that no matter who is in charge formally, a separate system — governed by targeting decisions, algorithms, and operating procedures — is able to expand and toggle between hidden, real-time, long-term tracking of individuals and high-profile, punitive enforcement intended to manage and criminalize communities of people based on the priorities of the moment.

Undermining sanctuary

There are numerous ways that criminalizing data is passed between local and federal law enforcement agencies. Many of these automated processes negate and circumvent hard-won “sanctuary” policies. These processes fly under the radar, taking the form of short-lived pilot programs and informal agreements that can turn into unnamed and normalized long-term practices that are embedded in technology and may even contradict formal policies.

New York is one case study in confusion. Most people, including some politicians in the state, think that local sanctuary laws prevent police collaboration with immigration enforcement. But since database sharing is automated across all 50 states, there is no true way to opt out of “collaboration.”

As the news site Documented reported, “New York state has a relatively robust sanctuary framework: only a single sheriff participates in the controversial 287(g) federal program, which deputizes local law enforcement officers — typically corrections personnel — to detain immigrants for questioning and arrests.Note en bas de page 42 A New York appellate court ruled that local law enforcement cannot honor ICE detainer requests to hold immigrants in custody for longer than their normal release times.Note en bas de page 43 Former state Governor Andrew Cuomo issued an executive order and amendment restricting state agencies’ cooperation with ICE.Note en bas de page 44

Yet, like every other US state, New York law enforcement officers and agencies use Nlets and NCIC, which pass on information (biographic or biometric) from everyone arrested for automated DHS database screening.

Separately, New York’s Division of Criminal Justice Services (part of the State Identification Bureau) also receives booking fingerprints, and they send them to ICE as well. Since 2005, DCJS has specifically notified ICE every time it receives fingerprints of a person who has previously been deported. In fact, according to the state agency’s 2009 annual report, DCJS would forward an electronic notice to LESC and a real-time Blackberry notification to ICE’s New York City fugitive apprehension unit.Note en bas de page 45 While the report and some of the technology described is old, the fundamental data-sharing structure is still in place. It remains DCJS policy to automatically forward a notification to ICE when a fingerprint taken by state authorities brings up a record that includes notice of a previous deportation.Note en bas de page 46

Similarly, since 2016 DHS’ Law Enforcement Notification System (LENS) program has allowed local law enforcement (including campus safety officers) at agencies nationwide (not just in New York) to subscribe to email alerts that flag when a migrant leaving ICE custody is released in or intends to settle within that law enforcement agency’s jurisdiction.Note en bas de page 47 That is on top of ICE sharing that information directly with State Identification bureaus and fusion centers, who in turn can notify local law enforcement agencies.

How automated criminalization works:

Street-level harassment and arrest by police is disproportionately focused on working-class Black and Latinx people, and therefore tends to screen out non- or less-criminalized populations from immigration records searches, which are initiated after arrest when a person’s fingerprints are booked. Once a person has their fingerprints booked, it is the discovery of any record that indicates foreign birth that triggers the IAQ and IAR process, which directs the weight of DHS inquiry and investigation onto that individual.Note en bas de page 48 By structuring its computer systems in this way, non-immigration law enforcement and DHS have succeeded in procedurally and extra-legally implicating birth abroad, and even international travel, as criminalizing.

Arrest and booking

Two main, known procedural pathways for automated migrant criminalization are dubbed in the parlance of law enforcement’s networked computer system the “Immigrant Alien Query” (IAQ) and “Immigrant Alien Response” (IAR). These are the computerized processes that automatically compare fingerprints collected by non-immigration police against DHS holdings in order to trawl an arrested person’s records for evidence of foreign birth, travel visa applications, historical border-crossings and previous encounters with immigration enforcement. These records, if dredged up, subject an arrested person to new or reinvigorated scrutiny, surveillance, harassment and potential arrest by ICE.

As mentioned above, database cross-checking with some DHS records became standard procedure in daily policing during the era of S-Comm implementation and has grown to encompass many more datasets since. Here, we detail a shortened version of this process, step-by-step. In the appendices, we provide a much longer detailed description of each step of this process and the databases involved.

- You get stopped by a cop. Maybe it is the result of a Stop-and-Frisk-type stop, or perhaps you were pulled over while driving a car with a broken taillight.

- The cop who stopped you demands your ID. In some states, refusing to give your name to a law enforcement officer, or not carrying government-issued identification, can itself lead to arrest.Note en bas de page 49

If you are carrying and hand over a US-issued ID or driver’s license, the cop is likely able, using the information on the ID, to access almost immediately your DMV records that provide biographical details, information about whether your license is valid or suspended, vehicle registration, car insurance information, and home address.

They, or a dispatcher, will also conduct a quick search for any open warrants that would show up in local, municipal and state databases.

- The cop may also decide to search your criminal history in additional federal databases. They may be able to conduct this search from their car or via mobile device, or ask a dispatcher to do it for them.

The databases they likely consult include: National Crime Information Center (NCIC) and Nlets

-

You are arrested and taken to jail for booking. Your fingerprints are automatically checked against state-level and FBI files. When your information and biometrics are loaded into the computer system, an automatic process is triggered. Your prints, photo, and biographical information are automatically forwarded to the State Identification Bureau (which are like FBIs at the state level that archive fingerprints and criminal history). Your biometrics are checked against FBI holdings, as well as the FBI’s NCIC and Next Generation Identification (NGI) biometric databases.Note en bas de page 50

Databases implicated: NGI and NCIC

ICE nerve centers: Law Enforcement Support Center and Pacific Enforcement Response Center

The Law Enforcement Support Center (LESC) and Pacific Enforcement Response Center (PERC) are two of a handful of ICE data centers that run 24/7 to follow as many leads as possible generated by the automated data criminalization process following a law enforcement encounter and database match. ICE claims that LESC workers process approximately 1.5 million biometric and biographic (IAQ) queries annually. Following a series of automated searches of at least sixteen visa, citizenship and criminal legal databases, the LESC analyst will recommend to an ICE deportation officer whether or not the person being searched may be removable, and whether a detainer, or immigration hold, could be issued.Note en bas de page 51 LESC works closely with law enforcement and local Field Offices to provide information about people who are held in custody and whom ICE may be able to target.

- Nlets checks your biometrics against DHS’ IDENT/ HART biometric database. If anything indicates that you might be foreign-born, your profile is forwarded on to ICE analysts via a biometric or biographic “Immigrant Alien Query,” or IAQ.

If DHS has any biometric record of you in its massive database — which may have come from applications for an immigration “benefit” like a travel visa, naturalization or asylumNote en bas de page 52 — then Nlets automatically creates a biometric “Immigrant Alien Query,” or IAQ, which notifies ICE and law enforcement of the “match.” Alternatively, a biographic IAQ is created if your biometric information cannot be matched to DHS’ holdings, but if you were born outside of the US (or if DHS’ records don’t show where you were born).

Both kinds of IAQ trigger a rapid and multi-step process created by ICE to automate the creation of detainers — a notice to law enforcement that ICE is supposedly investigating a person in law enforcement custody for violating immigration laws, and a request to notify ICE if that person is going to be released.

Databases used: IDENT/ HART

- ICE analysts at the Law Enforcement Support Center in Williston, Vermont receive the IAQ from Nlets.Note en bas de page 53 IAQs are placed in a queue. Once an IAQ rises to the top of the queue, a contract analyst for ICE picks it off of the line, conducts cursory initial database queries, and begins working on an Immigrant Alien Response (IAR). The contract analyst uses a computer system, ACRIMe, and oversees the process of checking you against numerous government and private datasets.Note en bas de page 54

- ACRIMe automatically searches for name and date of birth matches in various criminal, customs, and immigration databases.Note en bas de page 55

Databases and systems used and searched can include: ACRIMe, Nlets, CIS (Central Index System)Note en bas de page 56 , CLAIMS 3 and 4, EID (Enforcement Integrated Database), EAGLE (EID Arrest Graphical User Interface for Law Enforcement) , ENFORCE, ENFORCE Alien Removal Module (EARM), Prosecutions Module (PM), OM², Law Enforcement Notification System (LENS), EDDIE, IDENT/ HART, ADIS (Arrival and Departure System), SEVIS (Student and Exchange Visitor Information System), and EOIR (Executive Office for Immigration Review)

Court documents from 2017 indicated that ICE relies on sixteen databases.Note en bas de page 57 (This statement might downplay the fact that because many databases link to others, making contact with a system like EID may actually provide datasets from a dozen or more discrete databases.) - Based on the above searches, ICE’s data analyst at LESC decides whether ICE has the basis to issue a detainer or arrest you. The ACRIMe user finalizes the Immigration Alien Response (IAR) that recommends to an ICE deportation officer whether you might be removable.Note en bas de page 58 The IAR includes a person’s last known immigration or citizenship status, basic biographical information and criminal history. ACRIMe then electronically returns the IAR to both the requesting agency and the ICE ERO Field Office that is in the region of the requestor. If the analyst decides that a person might be deportable, then an ICE agent or officer can lodge a detainer via the ACRIMe system, and the IAR is routed to the local ICE field office which has jurisdiction.Note en bas de page 59 Whatever the decision, an ICE field office can still carry out its own search, and has unchecked power to decide when the “evidence” it has is enough to justify a detainer or arrest.Note en bas de page 60

- The IAR is sent from LESC to an ICE field office, and/or PERC. ACRIMe allows contract analysts at PERC to search multiple criminal legal, DHS and commercial databases to cross-check for any possibility of deportability. ICE field officers can access the analyst’s research via ACRIMe as well, and can also conduct their own research and investigation.

PERC is a newer center, established in January 2015.Note en bas de page 61 ICE contract analysts at PERC attempt to identify, locate, and build a case against people whom it suspects are deportable. This includes people who have been previously ensnared by the automated data criminalization system, but were released before ICE picked them up. PERC creates detainers all day and night, scraping datasets that collect everything from social media posts to family members’ naturalization records to try to justify “probable cause” for a detainer.

An ongoing lawsuit, Gonzalez v. ICE, called into question whether issuing detainers based on incomplete and inaccurate databases violates the constitution, and enjoined several states, temporarily preventing them from honoring PERC detainers. A Ninth Circuit ruling in September 2020 overturned the prior injunction, but as of February 2022, ICE agreed to honor the injunction voluntarily for a 6-month period (through August 2022) during settlement negotiations.Note en bas de page 62

Additional databases consulted by PERC analysts may include: Commercial databases CLEAR and/or LexisNexis - ICE uses ACRIMe to issue a detainer to the jail where you are held. Your fate is in the hands of your jailers.

Best case scenario: Even if the cops do not honor ICE’s detainer, and you are released, your “permanent record” is now beefed up and freshly linked to criminalizing data. If you encounter law enforcement or immigration officials in the future, it will only take a quick database check for them to decide that you’re worth detaining and investigating further. Also, ICE could decide at any time to prioritize coming for you. They have very updated information about where to find you.

Worst case scenario: If the jail decides to hold you or notify ICE about the details of your release, ICE could send over an agent to arrest you.

Anyone can be in a gang database

Allegations of gang membership — which may look like having your name show up in any of the various gang databases across the country — sweep more than a million people nationally into a feedback loop of data criminalization.

Different agencies define “gang” differently. NCIC defines a "gang" broadly: as “a group of three or more persons with a common interest, bond, or activity characterized by criminal or delinquent conduct.”Note en bas de page 63

Gang databases typify some of data criminalization’s most egregious characteristics. It is possible to be in a gang database and not know about it. Maintained in secret, with entries often based entirely on the subjectivity of a law enforcement officer, these databases track and share extra-legal and unproven information about alleged gang membership, listing the names of individuals convicted of “gang-related” crimes, as well as people who have not been convicted of anything but are alleged to be “associates.” If you are close to people who are alleged to be gang members, or if you simply exist in community with people profiled as gang members, your clothing choices or “frequenting gang areas” (even if these include your own home) are likely to land you in a gang database.Note en bas de page 64 Inclusion in a gang database makes you extra visible to police for harassment — and all police encounters can easily lead to arrest, further criminalization, and possibly deportation. Lack of transparency and procedures to challenge database entries makes it all but impossible to challenge your inclusion, and data sharing across agencies makes eradicating the taint of one-time inclusion nearly impossible.

The modern chapter of using alleged gang affiliation to enhance or multiply punishment dates back to at least the 1980s, when California began establishing gang injunctions — probation-like civil orders that target certain neighborhoods. If you’re hanging out or live in a targeted neighborhood, a gang injunction allows law enforcement to arrest you for standing on the corner with a member of your family or a friend.Note en bas de page 65 Once listed as a “gang member,” you may receive longer sentences if you do get convicted of anything.Note en bas de page 66 Accusations of gang affiliation can determine where you are incarcerated, and heighten your risk of violence in jail or prison, as well as in your country of origin if you are deported.Note en bas de page 67

Being criminalized as a gang member doesn’t end after your enhanced sentence. In states like California, a person who is convicted with a gang enhancement must register as a gang member for at least five years post-incarceration.Note en bas de page 68 If you are a noncitizen, gang affiliation can make you a DHS priority and ineligible for a green card, DACA, or other benefits, and potentially lead to your deportation. Indeed, it is not uncommon for ICE to continue pursuing someone indefinitely, even after they win their immigration case, based on asserted gang affiliation.Note en bas de page 69

The mid aughts saw the major expansion of gang database creation and sharing across federal agencies. In 2005, Congress established the National Gangs Intelligence Center (NGIC), an interagency network with representatives from the FBI, ICE, and CBP, among others.

Image Source Note en bas de page 70

Soon after the creation of NGIC, in 2007 Congress authorized the Gang Abatement and Prevention Act.Note en bas de page 71 The national database established pursuant to the 2007 bill became what is now GangNet — database software owned by a federal contractor, General Dynamics, which powers databases that contain personal information about “suspected gang members, including gang allegiance, street address, physical description, identifying marks, tattoos, photographs, and nationality.”Note en bas de page 72 Although GangNet itself has been superseded in importance by a more distributed and decentralized network of local, state, and regional gang information sharing initiatives, this section focuses on GangNet as the turning point in which data criminalization related to gang allegations shifted into a new phase, and in some ways it is emblematic of developments that have followed.

GangNet offers data analysis, facial recognition software, mapping, a field interview form, and a watch list. Using a single command, agencies can simultaneously search their own GangNet system and a network of GangNet systems in other states and federal agencies. ICE and the FBI, among other law enforcement agencies, use GangNet to track and share information across agencies.

For a short time during the Obama administration, ICE had its own ICEGangs database, based on the GangNet software. Its use was discontinued, and many ICE databases since include fields to input gang information, including EID and Palantir’s ICM. ICE agents can also access the FBI's National Crime Information Center (NCIC) — which has its own gang file connected to NGIC — in several different ways.Note en bas de page 73

Additionally, ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) stores gang investigation information in Palantir’s ICM, which is an upgraded version of CBP’s border entry-exit log database, TECS. The agency uses another Palantir product, FALCON, which accesses, duplicates, and reiterates alleged gang information from other key criminalization databases such as EID.Note en bas de page 74

At the local and state levels there are countless gang databases used and shared, from “in-house” county police departments to statewide databases like CalGang in California, which listed 80,000 people as gang members. A 2015 audit found that law enforcement “could not substantiate “a significant proportion of people in the database,” including dozens of infants tagged with “self-admission of gang membership.”Note en bas de page 68 In 2020, the state Attorney General revoked LAPD’s access to the state gang database due to CalGang’s egregious errors, and facing allegations of racial profiling.Note en bas de page 75 But LAPD continues to operate and update its own citywide gang database.Note en bas de page 76 And the Palantir products listed above allow cops to note and track “gang members” and perform searches — which cross-check local school district records and license plate location history — by entering in an alleged member’s name.Note en bas de page 77

Despite ongoing organizing against them, gang databases continue to be used by both police and ICE as methods and justification for targeting the people profiled in them. Because of database sharing and carve-outs in most legislation, local or state sanctuary laws don’t even attempt to protect people who are alleged to be gang members.

Stalking you now: Data brokers, cell phone apps, social media and GPS tracking

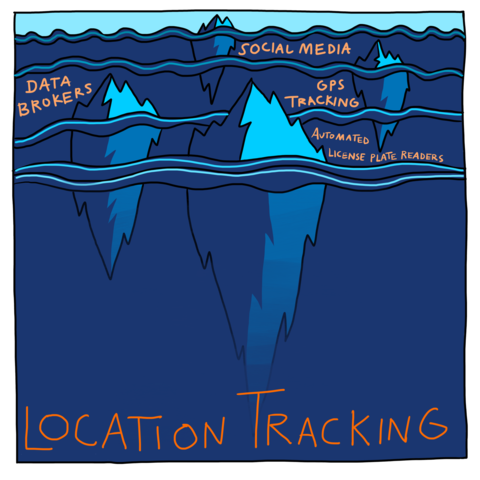

Location Tracking: Data brokers, automated license plate readers, social media and GPS tracking

As long as surveillance capitalists and others are permitted to steal and sell our real-time and historical location data, this information will be available to anyone who can buy it — including DHS and other government agencies.

As long as surveillance capitalists and others are permitted to steal and sell our real-time and historical location data, this information will be available to anyone who can buy it — including DHS and other government agencies.Note en bas de page 79

If you have a cell phone, you are being stalked and your personal data sold by multiple companies whose names you’ve likely never heard.Note en bas de page 80 So-called “third-party vendors” or data brokers like Venntel, Babel Street, Cuebiq, and LocationSmart collect real-time location data via GPS.Note en bas de page 81 They monitor your activities and movements through your phone via benign-seeming apps that use software development kits, or SDKs.Note en bas de page 82 Apps that use SDKs include weather apps, exercise monitoring apps, and video games.Note en bas de page 83 Third-party vendors provide SDKs to app developers for free in exchange for the information they can collect from them, or a cut of the ads they can sell through them. The aggregate information that apps collect can be extremely revealing.

There are endless examples of app data being used far outside of anyone’s initial understanding. For example, one third-party vendor, Mobilewalla, claimed to be able to track cellphones of protesters, and said it could identify protesters’ age, gender, and race via their cell phone use.Note en bas de page 84 In another case, historical location extracted by a data vendor from the gay hookup app, Grindr, was used by two reporters to “out” a top Catholic Church official.Note en bas de page 85

Law enforcement agencies regularly purchase criminal history reports, financial data from credit bureaus, and other personal data to profile people.Note en bas de page 86 For example, CBP purchases access to the Venntel global mobile location database via a portal, so that CBP officers can search a Venntel database to look for addresses or cell phones.Note en bas de page 87 DHS can also access cell phone location history from private databases that sell subscriptions or search platforms, such as LexisNexis and TransUnion.Note en bas de page 88

Some experts have noted that “anonymized” GPS location data is notoriously easy to cross-reference.Note en bas de page 89 A New York Times op-ed posed the question: “Consider your daily commute: Would any other smartphone travel directly between your house and your office every day?” The authors concluded: “In most cases, ascertaining a home location and an office location was enough to identify a person.”Note en bas de page 90 Indeed, cell phone location “pings,” collected by apps and stored under profiles tied to mobile ad IDs that are assigned to smartphones, were sufficient to identify individuals who ransacked the Capitol building in Washington, D.C., on January 6, 2020.Note en bas de page 91 And the prosecutorial use of “geo-fencing,” i.e. obtaining information from private companies about all persons in an area at a given time, has become exponentially more common in recent years.Note en bas de page 92

Biometrics: Cataloguing as control

Biometric Data Collection: "Facial recognition," "Voice prints," "Iris scans," "Fingerprints"

Data criminalization tracks and categorizes you relentlessly — but for that to be meaningful, you must be identifiable.

The origins of using biometric data to criminalize can be traced back to two key Victorian-era sociological practices: anthropometry, the cataloguing of national, metropolitan and colonial subjects based on physical measurements recorded by authorities and used to identify individuals; and eugenic ideas that physical attributes could prove racial inferiority as well as criminality (“mental degeneracy”) — which was thought to be a hereditary trait.Note en bas de page 93 Prisons, asylums, and forced sterilization were institutional responses to these 19th and early 20th century criminological concepts, and are the precursors to many of today’s carceral, “treatment”- and “reform”-based approaches to “criminal justice.”

Image Source Note en bas de page 94

During the last two decades since 9/11, biometric identification practices have become routine.

Our fingerprints, palmprints, faces, irises, voices, and gait are increasingly (and often secretly) recorded and used by commercial and government agencies, devices like our iPhones, and are purported to be incontrovertible, objective methods to prove our identities. Biometric identification methods are often trained on biased datasets.Note en bas de page 95 Algorithms can fail to account for changes in bodily appearance, dis/ability and gender, but as the nexus of biometric datasets expands and is able to cross-reference other tracking data, technologies such as facial recognition allow anyone who can access surveillance camera footage the ability to identify and track our movements in the world in real time.Note en bas de page 96

IDENT: DHS’ biometric data vacuum

DHS and CBP have heavily invested in biometric data theft and stalking as a primary method to surveil and criminalize all foreign-born people who enter into the US. Since the 1990s, the government has systematically collected and stored biometrics from immigrants.Note en bas de page 97 In 1994, DHS’ precursor established IDENT, or the Automated Biometric Identity System, to collect biometric data (at the time, fingerprints) from people accused of trying to enter the US without authorization.

IDENT became the central DHS-wide system for the storage and processing of biometric data, and after 9/11 it began including biometric records from people who have had any contact with DHS, including visa applicants at US embassies and consulates, noncitizens traveling to and from the United States, noncitizens applying for immigration “benefits” including asylum, migrants apprehended by CBP at the border or at sea, suspected immigration law violators encountered or arrested within the US, US citizens approved to participate in DHS's “trusted traveler” programs like Global Entry or TSA PreCheck, and people who have adopted children from abroad. IDENT also grandfathered into its database the fingerprint records for many naturalized US citizens who were fingerprinted before naturalizing, and noncitizens with current visas.

The future of IDENT = HART

HART is a present-day iteration of the anthropometric project which began with mugshots taken and catalogued in 1888.

HART is a present-day iteration of the anthropometric project which began with mugshots taken and catalogued in 1888.Note en bas de page 98

IDENT is expected to be replaced by the Homeland Advanced Recognition Technology (HART) system, a multi-billion dollar upgrade that would exponentially expand the agency’s capacity to collect, share and analyze a scaled-up and expanded range of biometric data, to be stored on Amazon Web Services’ GovCloud.Note en bas de page 99 (In this report, in order to make clear the evolution of this biometric system and reduce the number of acronyms, we refer to “IDENT/HART” when describing planned functionalities for the data system, and “IDENT” for current and previous versions of this data system.)

HART will dramatically expand DHS’ capacity to archive biometric data and search multiple modes simultaneously (face recognition and fingerprints at the same time, for instance). According to comments submitted to DHS’ Privacy Office by the Electronic Freedom Frontier, “DHS also plans to vastly expand the types of records it collects and stores to include at least seven different biometric identifiers, such as face and voice data, DNA, and a blanket category for ‘other modalities.’”Note en bas de page 100 HART allows its users to “ascertain the identity (1) of multiple people; (2) at a distance; (3) in public space; (4) absent notice and consent; and (5) in a continuous and on-going manner.Note en bas de page 101

HART will allow “latent fingerprints” (taken from surfaces, not just during booking) to be uploaded from non-immigration criminal punishment agencies. Latent prints can be archived for future searches.Note en bas de page 102 Like many DHS databases, it allows a user to subscribe to notifications if someone’s profile in HART logs a new “encounter” with DHS, or if other information in their record changes.

HART will draw directly from records created from travelers to and from the US, employment documents, and applications for other immigration “benefit” applications, as well as the FBI NGI system, which stores biometrics, including photographs, taken from state Department of Motor Vehicles.Note en bas de page 103 Similar to other DHS systems, HART will be used with other databases by DHS to collect and store “records related to the analysis of relationship patterns among individuals,” including “non-obvious relationships.” The data in the system will include records on US citizens and permanent residents as well as other non-citizens.Note en bas de page 104

Additionally, DHS spent hundreds of millions of dollars setting up state and local surveillance systems, including cameras in public places that record the daily routines and travel of millions of people.Note en bas de page 105 There are more than 30 million such surveillance cameras in the US; they are operated by both public agencies and private entities, and integrated with databases including the FBI’s main biometric repository, Next Generation Identification (NGI, formerly IAFIS) — which also feeds into various DHS databases.Note en bas de page 106

DHS under the Biden administration withdrew a Trump-era proposal that would have required more applicants (including children) for immigrant “benefits” such as asylum and student visas to submit an expanded range of biometric information including eye scans, voiceprints, DNA, and photographs for facial recognition.Note en bas de page 107 However, CBP and ICE continue to collect DNA from persons who are detained, using Buccal Collection Kits provided by the FBI Laboratory. CBP and ICE send the collected DNA samples to the FBI, which in turn process them and store the resulting DNA profile.”Note en bas de page 108

HART may become the largest biometric database in the US and the second largest in the world, and is eventually expected to store, potentially match and share DNA information.Note en bas de page 109 As a Just Futures Law report on HART notes, the database would “create a massive invasive catalog of the diverse physical characteristics of millions of US residents and people outside the United States.”Note en bas de page 110

Traveler and border surveillance

"Travel and Border Surveillance": Watchlists, Risk Prediction, Visas, "Overstay Leads"

The evolution of traveler surveillance by the US government is a cautionary tale showing how obsessive focus on “identification” technologies and automated “risk” prediction can normalize biometric data theft and the presumption of criminality until it is taken for granted and universally applied.

The evolution of traveler surveillance by the US government is a cautionary tale showing how obsessive focus on “identification” technologies and automated “risk” prediction can normalize biometric data theft and the presumption of criminality until it is taken for granted and universally applied.

There is no law or regulation that requires anyone to show any ID in order to fly domestically in the US.Note en bas de page 111 Yet, for most people, refusing to do so is a sure way to miss a flight, and can lead to arrest after the TSA calls the cops.

A good two decades before ICE figured out that it could circumvent search warrants by simply buying location and personal data from commercial third-party vendors, DHS’ precursor, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), was by 1998 already digitally stalking airline travelers using records created by online airplane ticket purchases, and profiling them based on their ticket-purchasing habits.Note en bas de page 112 By September 11, 2001, the government was already keeping files in a database that archived not only where you flew and when, but also the special meals you may have requested, the contact numbers you provided, and the itinerary of your journeys that did not involve air travel, such as bus and train rides.Note en bas de page 113

Before automated profiling became the norm in the criminal legal system to determine the “risk” level of people detained pretrial, and well before “constant vetting” algorithmic tools were used to predict which foreign exchange students may overstay their visas, CBP pioneered threat modeling software at US borders, rating the risk level of trade goods and people entering the country.

Traveler surveillance and border securitization, especially after 9/11, created a template for automated data criminalization practices that are widespread in criminal punishment and immigrant tracking systems today.

Early DHS digital stalking

Airline reservations have been computerized since the 1980s. As access to the Internet became a reality for more people during the 1990s, online flight reservations and other travel bookings created digital pathways for the federal government to track the movements of both citizens and non-citizens.

Over the decades, DHS sub-agencies and their predecessors accessed computerized reservation records from which they extracted Advance Passenger Information (API) and later, copies of complete Passenger Name Records (PNR) from airlines or third-party computerized reservations reservation systems.

Advance Passenger Information (API) includes information linked to the machine readable zone of passports and other travel documents, such as full name, date or birth, gender, passport number, country of citizenship, and country of passport issuance. Passenger Name Records (PNR) include the information that API records contain, and may also include a traveler’s home address, travel itineraries, credit card numbers, email addresses, IP addresses and timestamp, telephone numbers, emergency contact information, seat assignment, and other travel details. US Customs Service, a legacy organization of Customs and Border Patrol, began receiving API data voluntarily from air carriers in 1997, and after 9/11 demanded PNR data. This effectively gave DHS complete, aggregated mirror copies of the customer relationship management and transaction databases of the entire airline industry.

DHS also discovered that it could also acquire PNR data from third-party vendors to whom airlines outsourced booking; that arrangement foreshadows today’s warrant-free data-trawling via commercial data brokers.

By the late 1990s, the US Customs Service was using “computerized tools” to predict whether cargo entering, exiting, and transiting the US might violate US laws.Note en bas de page 114 Initially, risk-prediction tools were only used to screen conveyances and the people whose jobs it was to deliver trade goods. By 1999, all international travelers entering the US were evaluated like objects and profiled for “risk” by the agency’s black box analysis system. PNR data — that hodgepodge commercial airline archive of meal requests, bus trip itineraries, landline contact numbers, and credit card transactions — combined with records of border crossings, interactions with customs officers, and criminal legal data, were used as variables to screen for threats and fodder to train the algorithms. This was a key conceptual and legal shift.

Cashing in on “risk” after 9/11

“For terrorists, travel documents are as important as weapons.” — 9/11 Commission Report

The kind and amount of information collected from airline passengers who take flights within, to and from the US internationally — as well as even just over the US — changed dramatically after 9/11. While travel by non-US citizens had long been treated as inherently suspicious, prior to 9/11, most US citizens were used to traveling without being treated like a potential terrorist. Overnight, that changed. The presumption that a traveler had a legal claim to privacy and free movement, unimpeded by invasive bodily searches and x-ray scans, was replaced by the now-normal protocols that we all routinely endure in order to board a flight. While long lines, pat-downs and shoe removals are annoying for everyone, few of us have realized the ways that we’re surveilled before and after we leave the airport, and how the extent to which we’re constantly evaluated as security threats (in real time, by multiple, interlocking systems) legitimates the ever-expanding surveillance apparatuses of state and social control.

After 9/11, the federal government ramped up its data-collecting, database-sharing, automated predictive threat modeling and terrorist risk profiling. It beefed up its biometric identification technologies and partnerships with commercial entities that secretly collect, retain and sell consumer data for profit. It was a perfect storm: the World Trade Center attacks allowed the government to exceptionalize sites of travel (especially international flights) as deserving of extreme surveillance; meanwhile, big data collection and analysis industries, facilitated by growing Internet and cell phone use, were handed billions of dollars in research and development funds, and enjoyed little to no oversight as they churned out new data-collecting and prediction technologies. The US government spent at least $2.8 trillion on counterterrorism related efforts between 2002 and 2017, granting contracts to old time war profiteers like Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman — but also to tech and Silicon Valley giants such as Amazon, Google, and Palantir Technologies.Note en bas de page 115

Meanwhile, agencies that administratively managed visas for temporary stays, citizenship and naturalization were reorganized into a more bellicose Department of Homeland Security. DHS bulked up its biometric database, IDENT (now in process of upgrading to HART), by requiring biometric data collection at every point along the border and ports of entry—and extending well outwards from the national border line — from all people entering or exiting the country, non-citizens and citizens alike.

Between 2001 and 2014, IDENT added new categories of people to a list of “national security interest:” people who had any contact with DHS, related agencies, and other governments; visa applicants at US embassies and consulates; noncitizens traveling to and from the United States; noncitizens applying for immigration “benefits” (including asylum and short-term visas); unauthorized migrants apprehended at the border or at sea; suspected immigration law violators encountered or arrested within the US; and even US citizens approved to participate in DHS's “trusted traveler” programs or who adopted children from abroad.

Between 2001 and 2014, IDENT added new categories of people to a list of “national security interest:” people who had any contact with DHS, related agencies, and other governments; visa applicants at US embassies and consulates; noncitizens traveling to and from the United States; noncitizens applying for immigration “benefits” (including asylum and short-term visas); unauthorized migrants apprehended at the border or at sea; suspected immigration law violators encountered or arrested within the US; and even US citizens approved to participate in DHS's “trusted traveler” programs or who adopted children from abroad. IDENT now trolls all migrants who come to the US.

Each time that an individual’s biometric identifier is uploaded to the IDENT database by an agent for ICE, CBP, Citizenship and Immigration Services (CIS), or the Department of State, IDENT would log the data transfer as an “encounter.”Note en bas de page 116 In the circular loop of data criminalization, each of these “encounters” (which really just indicate that a person may be a non-US citizen traveler or migrant) comes up as criminalizing material when in future searches by law enforcement that data automatically flags a person for ICE agents and LESC analysts who are searching for deportability. In this way, “encounters” that fail to prove administrative law-breaking nonetheless confer suspicion on a person, marking them and even their contacts for ongoing surveillance and repeated harassment.

In this way, “encounters” that fail to prove administrative law-breaking nonetheless confer suspicion on a person, marking them and even their contacts for ongoing surveillance and repeated harassment.

CBP’s current surveillance system relies on compelled and often covert biometric identification and constant vetting against criminalizing databases during travel — using “a traveler’s face as the primary way of identifying the traveler to facilitate entry and exit from the United States” via CBP apps, kiosks for “trusted traveler” programs and security camera live feeds.Note en bas de page 117 The goal, then-CBP Commissioner Kevin McAleenan declared in 2018, is to “confirm the identity of travelers at any point in their travel,” not just at entry to or exit from the United States.Note en bas de page 118

Soon, if not already, DHS and other law enforcement agencies will be able to access more experimental modes of biometric via cloud-based IDENT/HART, to link fingerprints, palm prints, iris scans, and photographs with biographic information to construct detailed and holistic portraits. This trove of biometric data, in turn, will likely be fodder to develop and train newer technologies as they emerge.

How automated traveler surveillance works

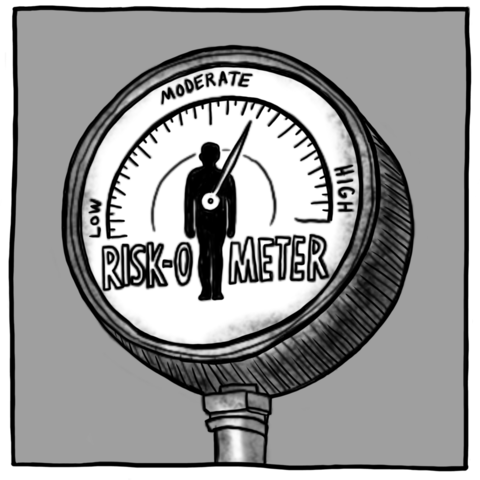

"Risk-o-meter"

Today, all passengers are pre-screened before even stepping into an airport. You are designated “low risk” only if you have already submitted to and passed a “trusted traveler” clearance program. You might be profiled as an “unknown risk” if you did not qualify for “trusted traveler” status, or you might be deemed “high risk” based on the secret and fluctuating rules created by DHS programs like “Silent Partner” and “Quiet Skies.” These programs are mutant descendants from the War on Terror: TSA does not claim that the people who are flagged by the programs are known or suspected terrorists, and claims that being assessed as a risk does not leave a derogatory mark on a person’s record; nonetheless, being flagged by a TSA rule opens up a person’s profile for close scrutiny as the entirety of their digital histories are cross-referenced with criminalizing records — and the designation, whether or not temporary, will be noted for the future.

Anyone who is crossing a US border or traveling internationally by air, either to, from, within, or over the US is subjected to travel surveillance via:

- database-matching to watchlists and “derogatory information” stored in criminalizing government databases, updated multiple times from the time of booking until travel ends

- Internet stalking by commercial ticketing and reservation systems and airlines — all of which share information with DHS

- Real-time biometric identification and location-tracking during travel by cameras operated or accessed by airlines and CBP

- In-person interrogations and searches during travel and at border crossings

CBP uses travel industry IT and communications vendors databases and systems to siphon information as well as to control the movements of travelers in real time by denying entry or requiring in-person screening.Note en bas de page 119

“Life cycle” of international travel surveillance

As mentioned above, the process of screening all people who travel to, from, within, or even over the US begins well before anyone steps into an airport. Surveillance, identification, cross-checking and prediction processes may begin with the click of a mouse on someone’s home computer in a country far away. Here, we detail a shortened version of this process, step-by-step. We also have a longer version of this process written-up in more detail as an appendix.

- If you are a non-citizen, before you can legally enter the US you must apply for a visa and/or have your passport checked. If you were born in one of the 38 countries that qualify for the US’ visa waiver program, you don’t need a visa for some short-term visits.

If you were born in a country that is not eligible for visa waivers, you must obtain authorization, in the form of a non-immigrant or immigrant visa, from the US Department of State (DOS), issued at an US Embassy or Consulate. Visa applications automatically generate multiple biographic and biometric checks against multiple criminalizing and suspected terrorist databases that seek to verify an applicant’s identity and match them to derogatory information.Note en bas de page 120

Databases used to approve or “vet” visas: Electronic System for Travel Authorization (ESTA) and Consular Consolidated Database (CCD).

Additionally, CBP’s National Targeting Center (NTC) “continuously vets” all holders of immigrant and non-immigrant visas of travelers before they board US-bound flights. - As soon as you purchase your airline ticket, your reservation information and itinerary become available to DHS.

This information is stored and retrievable as the following data: Passenger Name Record (PNR) - Your personal profile and information — your name, ethnicity, national origin, travel itinerary, occupation, personal, political, religious and professional contacts and associations — can be screened by DHS using black-box, rules-based algorithmic predictions as well as matched against various secret watchlists. These secret and changing rules determine whether and how you may be targeted for harassment and arrest once you do show up at the airport.

In November 2001, then-President Bush signed the Aviation and Transportation Security Act into law, creating the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) — a division of DHS that operates a travel-permission system for domestic US flights called “Secure Flight.”

“Secure Flight” began as a program where aircraft operators screened names from passenger reservations to see if they matched or closely resembled any included on a “No Fly List”Note en bas de page 121 and other federal watchlists of “known or suspected terrorists” created by the FBI. If the aircraft operator suspected a watchlist match, the operators were supposed to notify TSA and send the targeted passenger for enhanced in-person screening.

Today, “Secure Flight” allows TSA to access CBP’s surveillance dragnet and prediction tool — Automated Targeting System, or ATS, (more on this below) and write rules for the algorithm used by the ATS system to decide who qualifies as a “risk” and will be added to a category of people who will be subject to increased security checks. Targeting rules, and therefore the people targeted, can change day to day.Note en bas de page 122

According to a 2019 PIA on ATS: “These rules are based on risk factors presented by a given flight and passenger, the level of screening for a passenger that may change from flight to flight. Travelers may match a TSA or CBP-created rule based upon travel patterns matching intelligence regarding terrorist travel; upon submitting passenger information matching the information used by a partially-identified terrorist; or upon submitting passenger information matching the information used by a Known or Suspected Terrorist.”Note en bas de page 123

Data systems you are screened against and processed by may include:

- Secure Flight

- Various FBI “no fly lists,” including “known or suspected terrorists”

- Automated Targeting System (ATS): more below

- ICM/ TECS

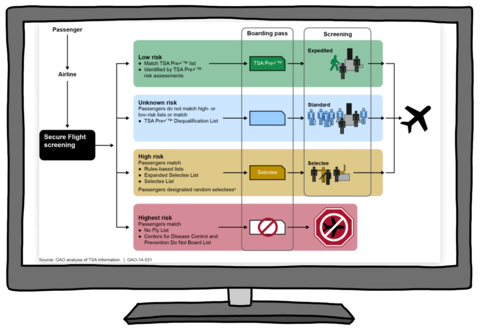

Image Source Note en bas de page 124

Passenger, Airline, Secure Flight Screening; Low risk: Match TSA Precheck list, Identified by TSA precheck final assessments; Unknown risk: Passengers do not match high- or low- risk lists or match TSA Precheck Disqualification List, High Risk: Passengers Match, Rules-based lists, Expanded Selectee List, Selectee List, Passengers designated random selectees, Highest Risk: Passengers match, No Fly List, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Do Not Board List

- Once you are inside the airport, your face is overtly and covertly captured for facial recognition and real-time tracking.

CBP uses its own in-house facial recognition matching technology, the Traveler Verification Service (TVS), for identity verification and biometric entry and exit “vetting checks.”Note en bas de page 125

When the traveler enters or exits an airport, border crossing, or seaport, they will pass a camera connected to CBP’s cloud-based TVS facial matching service. The camera may be owned by CBP, the air or vessel carrier, another government agency (like TSA), or an international partner.Note en bas de page 124 If the camera is CBP-owned and operated, a CBP officer will be present.

However, if the camera is airline-operated, it may not necessarily be visible. It may be located on a jetway after a passenger scans their boarding pass, and the passenger might not even know an image of their face is being captured. TVS matches the live image of the traveler on the jetway with existing photos in a “gallery” (maintained in IDENT) that archives photographs from CBP’s ATS-UPAX database that might be from previous exits and entries, US passports and visas, from DHS apprehensions, enforcement actions, or other immigration-related records.

If your face does not match existing DHS records, you are flagged for scrutiny as well. A CBP website provides the following example:

“The biometric system alerted the officers because when preflight information was gathered on the woman, no historical photos to match against her could be found.

A CBP officer took the woman aside and looked at her passport. No visa was attached and the woman didn’t have a green card to prove she was a lawful permanent resident. Upon further questioning, the woman admitted that four years ago, she had come into the country illegally.

Using a specially designed, CBP biometric mobile device, the officer took fingerprints of the woman’s two index fingers. ‘This was the first time that we had captured this individual’s biometrics, her unique physical traits,’ said Bianca Frazier, a CBP enforcement officer at the Atlanta Airport. ‘We didn’t have her biometrics because we had never encountered her before.’”Note en bas de page 126 - CBP must approve every single passenger before an international flight departs, arrives in, or overflies the US. When you check in for an international flight to, from, or that overflies the US, the Advance Passenger Information System (APIS) transmits your PNR data and itinerary (including flight status updates) to CBP. Before you are permitted to board the plane, your passport or ID is scanned by a CBP officer or TSA agent. The machine readable zone of your document pulls up your full name, date of birth, and citizenship, which can be used to retrieve information about your scheduled flight. This data is sent to CBP via APIS in the form of “passenger manifests” — commercial airline records that are transferred to CBP for vetting in real-time, or 30 minutes prior to boarding.Note en bas de page 127 APIS generates a “Overstay Lead” list that is shared with CBP’s main computer system that assesses “risk,” ATS (more on this below).Note en bas de page 128

Inside DHS’ future-prediction arsenal

Technologies are always upgrading. Here, we examine more closely two data systems that incorporate multiple future-facing elements, including geospatial and relationship-mapping visualizations and “trend detection” in addition to “risk” prediction.

Automated Targeting System (ATS)

As mentioned earlier, Automated Targeting System (ATS) is one of the most important connective databases for current migrant data criminalization processes. CBP uses ATS to assess “risk” and track travelers and import trade goods.Note en bas de page 130 CBP’s National Targeting Center uses ATS to conduct “continuous vetting” of valid US immigrant and nonimmigrant visas, and uses data from immigration, law enforcement, commercial, and open-source databases to predict “risk.”Note en bas de page 131 Continuous vetting occurs in real-time and describes the process by which ATS alerts CBP, for instance, if a traveler’s ID check at a foreign airport brings up biographical or biometric matches to any records in criminalizing databases — including those that track immigration violations, the FBI’s Terrorist Screening Database (TSDB) and outstanding wants and warrants.Note en bas de page 132 All the people who categorically fit CBP’s targeting rules are flagged by ATS, and these individuals are then reviewed by CBP officers. CBP can then issue a “no board” recommendation to prevent someone’s travel to the US, or recommend the State Department revoke a visa.

ATS’ black-box algorithms are based on criteria and rules developed by CBP, to match people and trade goods against “lookouts” and data-scrape personal information from various linked databases to identify “patterns of suspicious activity” and predict potential terrorists, transnational criminals, people who may be inadmissible to the US under US immigration law, and “persons who pose a higher risk of violating US law.”Note en bas de page 132 ATS has built its dataset over decades, well before 9/11. ATS-Passenger (ATS-P), a legacy subsystem of ATS, has been used to screen international passengers on planes, trains and ships since the 1990s — although data collection for ATS overall was expanded and automated since 2002.Note en bas de page 133 ATS-P is now being upgraded to UPAX, which more seamlessly integrates databases by showing records from multiple systems and incorporating information from third-party databases and the Internet.Note en bas de page 132

In order to train its risk assessment, ATS uses data including: bills, entries, and entry summaries for cargo imports; shippers’ export declarations and transportation bookings and bills for cargo exports; manifests for arriving and departing passengers and crew; airline reservation data; nonimmigrant entry records; and records from “secondary referrals,” CBP incident logs, suspect and violator indices, state Department of Motor Vehicle Records, and seizure records.

Every person who leaves or enters through a US border is subject to ATS’ risk assessment, and while different linked databases claim to delete data at different times, much ATS data is kept for decades, whether in ATS’s databases or mirrors and backups in other DHS systems.

Like other data criminalization tools, ATS draws heavily from NCIC data — but it also surveils people who have never had an encounter with police.Note en bas de page 134 A speaker at a 2004 Customs Budget Authorizations hearingNote en bas de page 135 testified that ATS data scrapes airline passenger information to look for “anomalies and red flags.” Since “red flags” are determined based on rules for ATS that are created by CBP, these rules allow CBP to expand the list of what is considered suspicious activity to encompass any number of legal behaviors.Note en bas de page 136 People who are deemed “high risk” by ATS are flagged for further scrutiny and sent to secondary screening at US border and airport checkpoints. Those encounters lead to the generation of yet more data criminalization records, in the form of risk assessments retained by ATS, which are fed into the targeting algorithm that could alert a TSA or CBP agent the next time the person’s passport is scanned.

Since “red flags” are determined based on rules for ATS that are created by CBP, these rules allow CBP to expand the list of what is considered suspicious activity to encompass any number of legal behaviors.

The evolution of ATS’ targeting rules reveals the trajectory of terrorism and surveillance rhetoric. Mass surveillance that began as exceptional (the post-9/11 period) and provisional (pilot programs at 15 airports) is now routine — and probable cause for law enforcement intervention (which can end in arrest and deportation) includes not only subjective suspicion but fully abstracted prediction mathematics. Today, ATS is utilized by CBP to predict who might violate US immigration (not just anti-terrorism) laws: ATS data is used to generate an “Overstay Hotlist,” which is a list of “overstay leads” derived from information obtained through travel records.Note en bas de page 137 (More on this below.)